My father would lift me

to the ceiling in his big hands

and ask, How’s the weather up there?

And it was good, the weather

of being in his hands, his breath

of scotch and cigarettes, his face

smiling from the world below.

O daddy, was the lullaby I sang

back down to him as he stood on earth,

my great, white-shirted father, home

from work, his gold wristwatch

and wedding band gleaming

as he held me above him

for as long as he could,

before his strength failed

down there in the world I find myself

standing in tonight, my little boy

looking down from his flight

below the ceiling, cradled in my hands,

his eyes wide and already staring

into the distance beyond the man

asking him again and again,

How’s the weather up there?

~George Bilgere “Weather”.

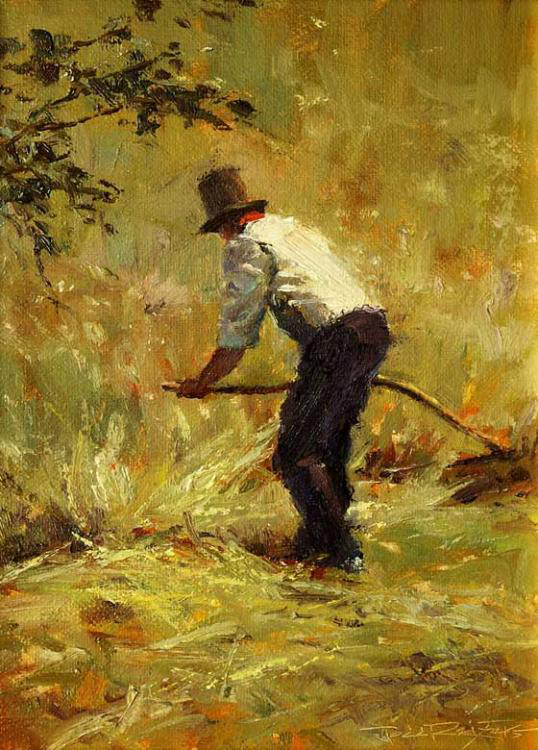

It was hard work, dying, harder

than anything he’d ever done.

Whatever brutal, bruising, back-

breaking chore he’d forced himself

to endure—it was nothing

compared to this. And it took

so long. When would the job

be over? Who would call him

home for supper? And it was

hard for us (his children)—

all of our lives we’d heard

my mother telling us to go out,

help your father, but this

was work we could not do.

He was way out beyond us,

in a field we could not reach.

~Joyce Sutphen “My Father, Dying”

Deep in one of our closets is an old film reel of me about 16 months old sitting securely held by my father on his shoulders. I am bursting out with giggles as he repeatedly bends forward, dipping his head and shoulders down. I tip forward, looking like I am about to fall off, and when he stands back up straight, my mouth becomes a large O and I can almost remember the tummy tickle I feel. I want him to do it again and again, taking me to the edge of falling off and then bringing me back from the brink.

My father was a tall man, so being swept up onto his shoulders felt a bit like I was touching heaven.

It was as he lay dying 30 years ago this summer that I realized again how tall he was — his feet kept hitting the foot panel of the hospital bed my mother had requested for their home. We cushioned his feet with padding so he wouldn’t get abrasions even though he would never stand on them again, no longer towering over us.

His helplessness in dying was startling – this man who could build anything and accomplish whatever he set his mind to was unable to subdue his cancer. Our father, who was so self-sufficient he rarely asked for help, did not know how to ask for help now.

So we did what we could when we could tell he was uncomfortable, which wasn’t often. He didn’t say much, even though there was much we could have been saying. We didn’t reminisce. We didn’t laugh and joke together. We just were there, taking shifts catching naps on the couch so we could be available if he called out, which he never did.

This man:

who had grown up dirt poor,

fought hard with his alcoholic father

left abruptly to go to college – the first in his family –

then called to war for three years in the South Pacific.

This man:

who had raised a family on a small farm while he was a teacher,

then a supervisor, then a desk worker.

This man:

who left our family to marry another woman

but returned after a decade to ask forgiveness.

This man:

who died in a house he had built completely himself,

without assistance, from the ground up.

He didn’t need our help – he who had held tightly to us and brought us back from the brink when we went too far – he had been on the brink himself and was rescued, coming back humbled.

No question the weather is fine for him up there. I have no doubt.

Make a one-time or recurring donation to support daily Barnstorming posts

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is deeply appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly