(written after a February storm in 2006)

(written after a February storm in 2006)

I awoke to eery inky darkness this morning around 5 AM. No digital clock numbers shining red, no nightlight illumination. Just black. The wind and rain storm during the night had left us without power, and a quick scan out the windows informed me we were not alone. The closest lights in the horizon were toward Lynden 6 miles away, and the Canadian border cities ten miles away all gleamed bright.

The flashlights, of course, were not where they were supposed to be, and the candles were stuck deep in cupboards after Christmas, so I stumbled around in the dark, feeling my way through now unfamiliar hallways and rooms, gathering up what was needed to provide a little light and safety. When an Amish acquaintance from Ohio called me a couple hours later and I lamented about how completely unAmish I was in my dependency on the power grid, he chuckled and asked me if I had my oil lamps lit yet.

We are nearing 24 hours since the power went out, the storm long past, but sit with 200,000 other homes waiting to be “turned on” again. It could be awhile. It is just for these kinds of situations on the farm that we have a small generator that we use sporadically to pump the water to the barn and keep the freezer and refrigerator cold. I’m stealing a little generator power to write this quickly.

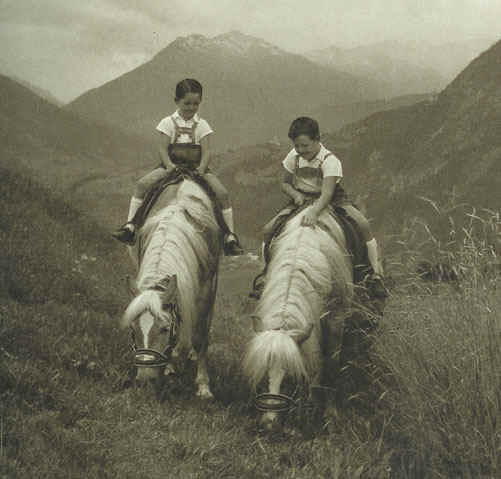

Our children have always celebrated our power outages. It is high adventure, an escape from the routine, and even in their teenage years, they cling closer. It managed to be an atypical “family” Saturday, whereas we usually are bustling about separately playing catch-up from the week, and preparing for the activities of the week to come. Instead, today we cleaned barn with the help of flashlights, cleaned house together and folded clothes in the dark, guessing the color of the dark socks, played piano and sang together and read lines in my son’s high school musical, helping him to memorize his part. We played games and laughed more than usual. We were drawn together by necessity as well as by choice. There was one good light in the kitchen, so there we sat encircled together, connected by a candle, when so often we are flung apart by the busyness and bright light of the world.

I am wistful about the thought of the power returning sometime tonight or tomorrow. My children said it was one of the best Saturdays they remember in a long time. I have to agree. Maybe we need to take a hint and shut off the electronics– the TV, this computer, and just sit down together more often, sharing ourselves inside a circle of light. It is far more memorable, and in a chilly house battered by a windstorm, far more warming to the heart.