May the wind always be in her hair

May the sky always be wide with hope above her

And may all the hills be an exhilaration

the trials but a trail,

all the stones but stairs to God.

May she be bread and feed many with her life and her laughter

May she be thread and mend brokenness and knit hearts…

~Ann Voskamp from “A Prayer for a Daughter”

“I have noticed,” she said slowly, “that time does not really exist for mothers, with regard to their children. It does not matter greatly how old the child is – in the blink of an eye, the mother can see the child again as she was when she was born, when she learned to walk, as she was at any age — at any time, even when the child is fully grown….”

~Diana Gabaldon from Voyager

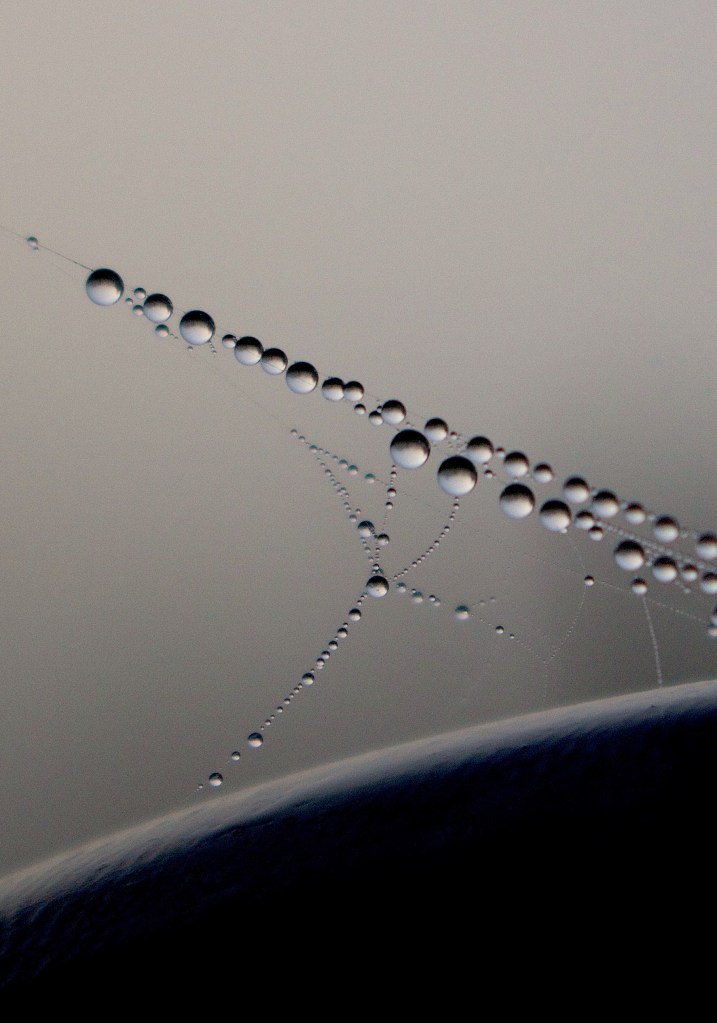

Your rolling and stretching had grown quieter that stormy winter night

thirty-three years ago, but still no labor came as it should.

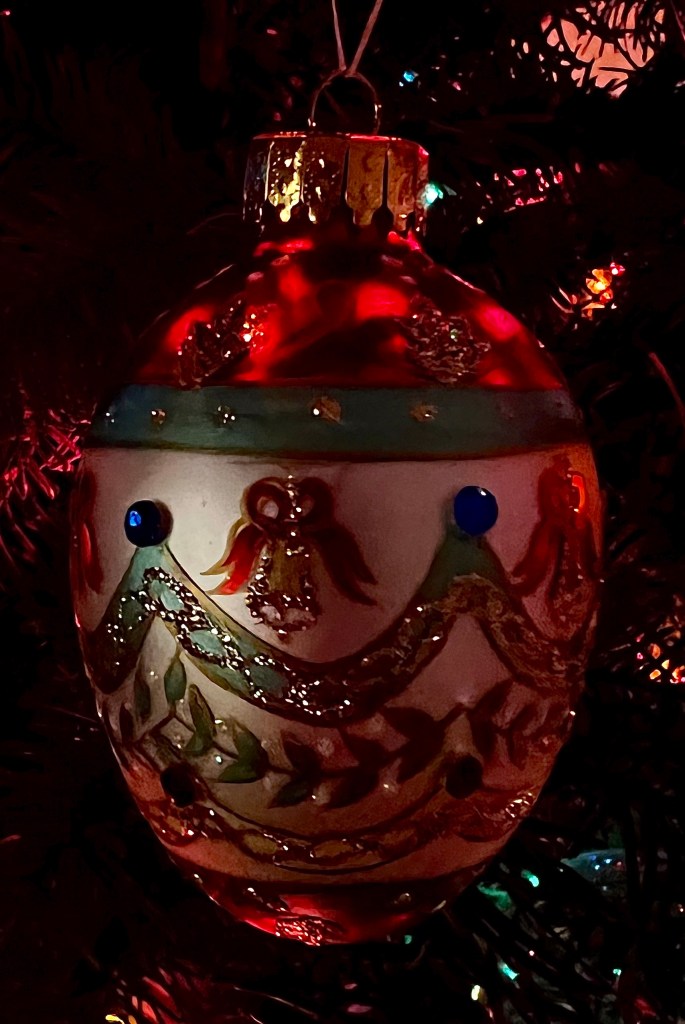

Already a week overdue post-Christmas,

you clung to amnion and womb, not yet ready.

Then as the wind blew more wicked

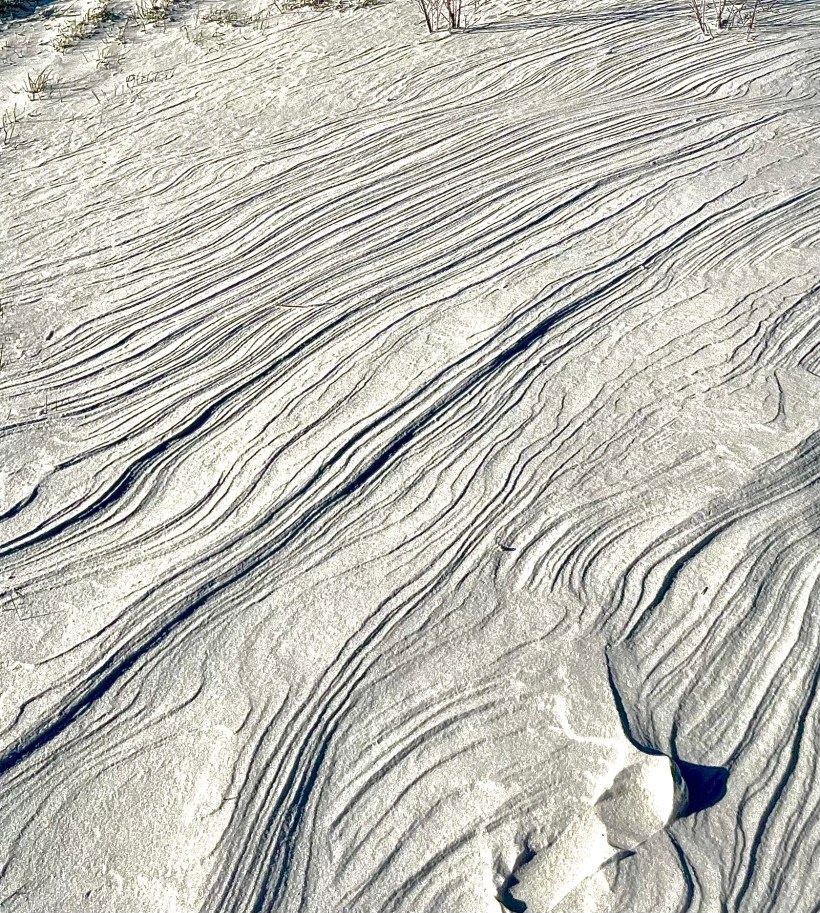

and snow flew sideways, landing in piling drifts,

the roads became more impassable, nearly impossible to traverse.

So your dad and I tried to drive to the hospital,

concerned about your stillness and my advanced age,

worried about being stranded on the farm far from town.

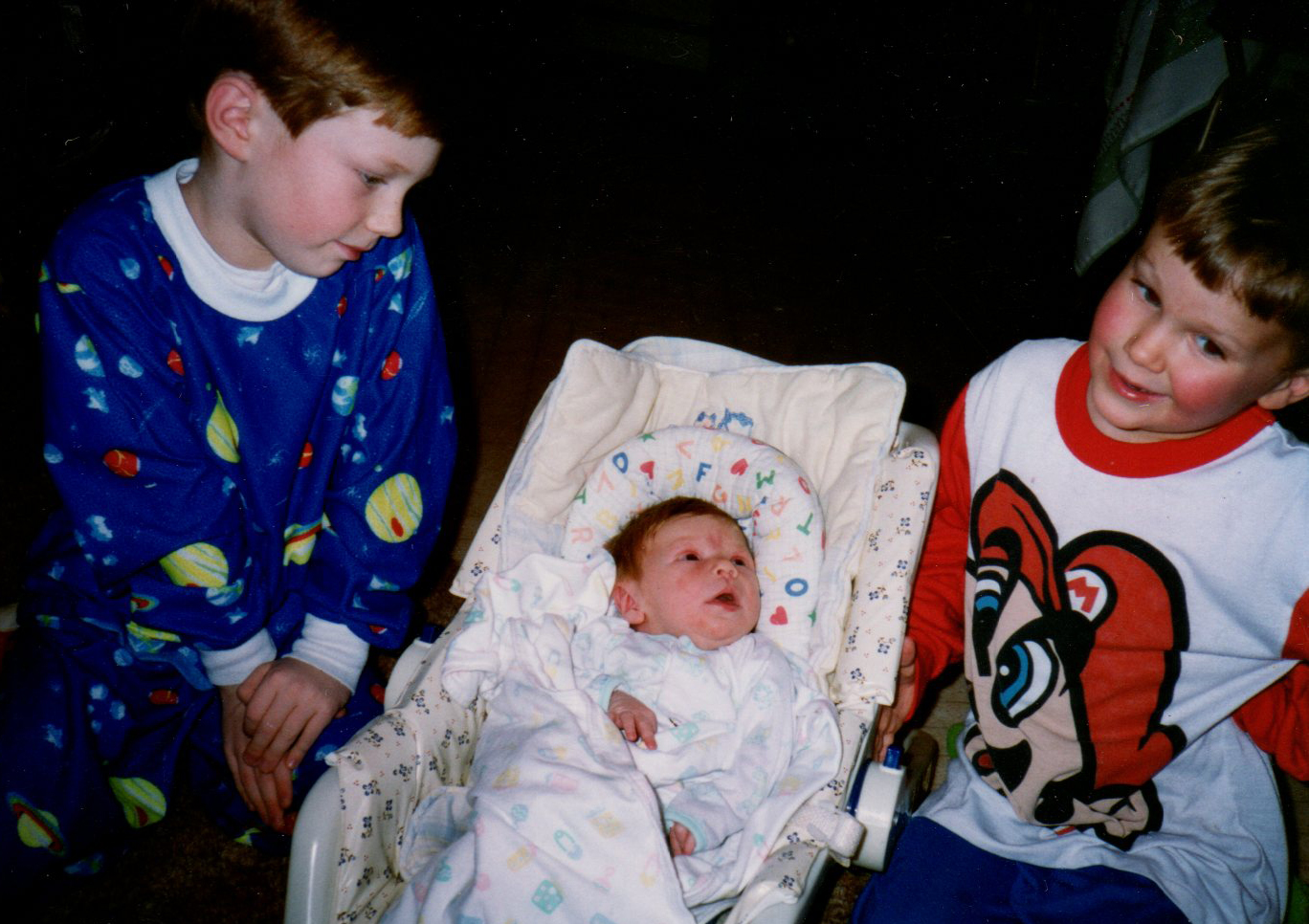

When a neighbor came by tractor to stay with your brothers overnight,

we headed down the road and our car got stuck in a snowpile

in the deep darkness, our tires spinning, whining against the snow.

Another neighbor’s earth mover dug us out to freedom.

You floated silent and still, knowing your time was not yet.

Creeping slowly through the dark night blizzard,

we arrived to the warm glow of the hospital,

your heartbeat checked out steady, all seemed fine.

I slept not at all.

The morning’s sun glistened off sculptured snow as

your heart ominously slowed.

You and I were jostled, turned, oxygenated, but nothing changed.

Your heart beat even more slowly,

threatening to let go your tenuous grip on life.

The nurses’ eyes told me we had trouble.

The doctor, grim faced, announced

delivery must happen quickly,

taking you now, hoping we were not too late.

I was rolled, numbed, stunned,

clasping your father’s hand, closing my eyes,

not wanting to see the bustle around me,

trying not to hear the shouted orders,

the tension in the voices,

the quiet at the moment of opening

when it was unknown what would be found.

And then you cried. A hearty healthy husky cry,

a welcomed song of life uninterrupted.

Perturbed and disturbed from the warmth of womb,

to the cold shock of a bright lit operating room,

your first vocal solo brought applause

from the surrounding audience who admired your purplish pink skin,

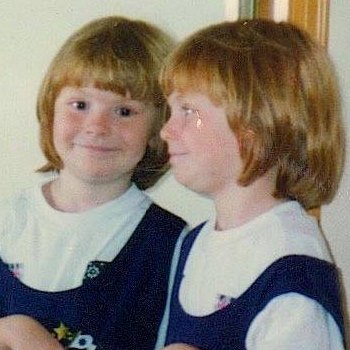

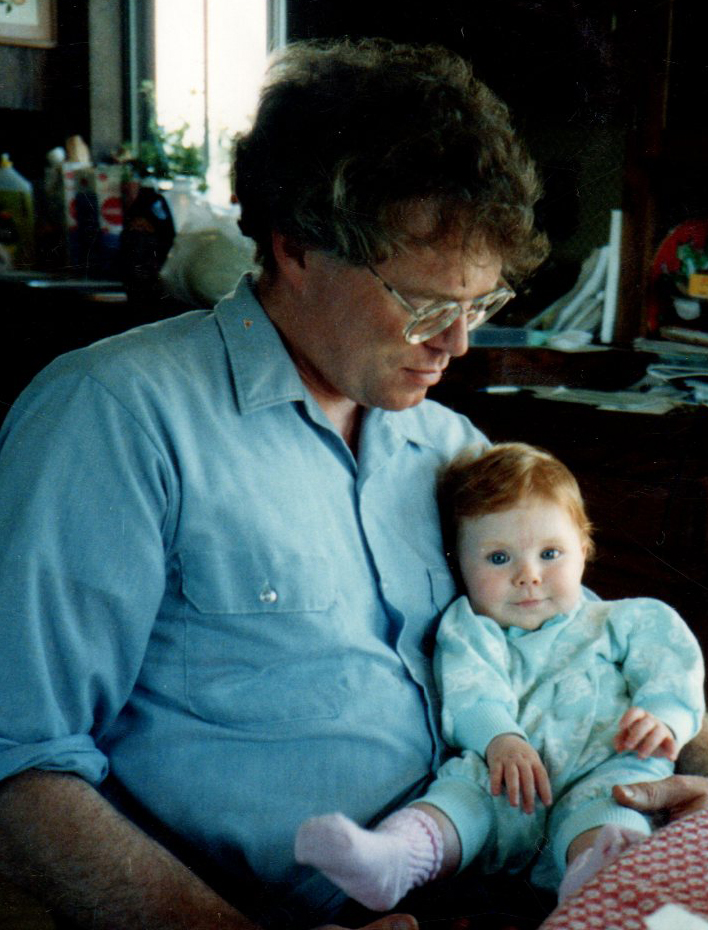

your shock of damp red hair, your blue eyes squeezed tight,

then blinking open, wondering and wondrous,

emerging and saved from a storm within and without.

You were brought wrapped for me to see and touch

before you were whisked away to be checked over thoroughly,

your father trailing behind the parade to the nursery.

I closed my eyes, swirling in a brain blizzard of what-ifs.

If no snow storm had come,

you would have fallen asleep forever within my womb,

no longer nurtured by my failing placenta,

cut off from what you needed to stay alive.

There would have been only our soft weeping,

knowing what could have been if we had only known,

if only God had provided a sign to go for help.

So you were saved by a providential storm sent from God

and we were dug out from a drift:

I celebrate whenever I hear your voice –

your students love you as their teacher and mentor,

you are a thread born to knit and mend hearts,

all because of the night God sent drifting snow.

My annual retelling of a most remarkable day::

Thirty-three years ago today, our daughter Lea Gibson was born in an emergency C-section, hale and hearty because the good Lord sent a wind and snow storm to blow us into the hospital in time to save her.

Thanks to that blizzard, Lea is a school teacher, serves the youth ministry in her church, and will soon receive her Masters in School Counseling.

She is married to her true love Brian– he also is a blessing sent from the Lord. Together they have their own miracle child, happily born in the middle of the summer rather than snow-drift season.

The Lord wanted her in this world:

May she be bread and feed many with her life and her laughter

May she be thread and mend brokenness and knit hearts…

Make a one-time or recurring donation to support daily Barnstorming posts

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is deeply appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly