…we all suffer.

For we all prize and love;

and in this present existence of ours,

prizing and loving yield suffering.

Love in our world is suffering love.

Some do not suffer much, though,

for they do not love much.

Suffering is for the loving.

This, said Jesus, is the command of the Holy One:

“You shall love your neighbor as yourself.”

In commanding us to love, God invites us to suffer.

Over there, you are of no help.

What I need to hear from you is that you recognize how painful it is.

I need to hear from you that you are with me in my desperation.

To comfort me, you have to come close.

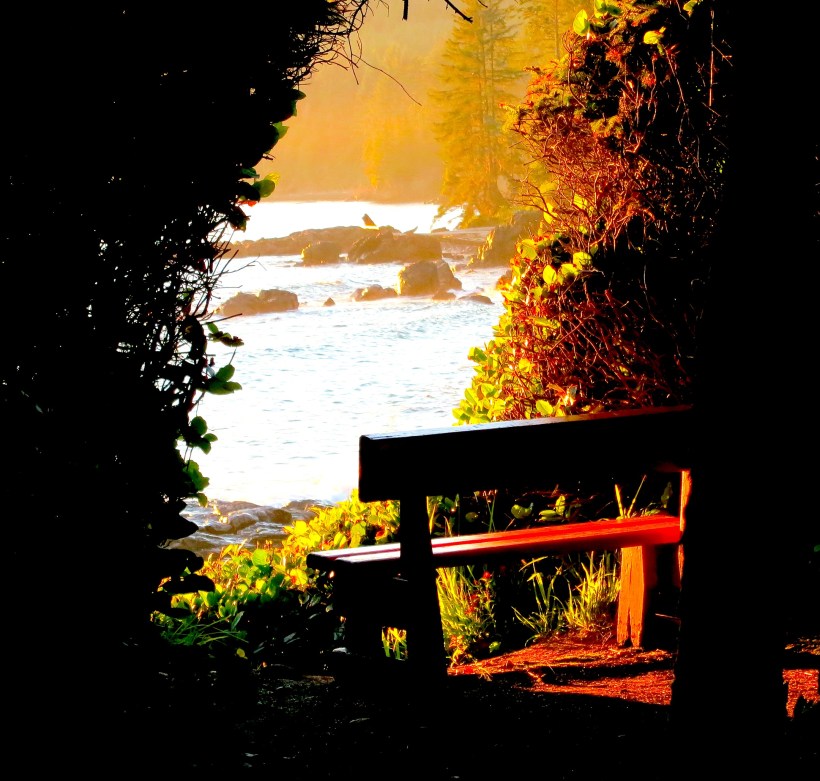

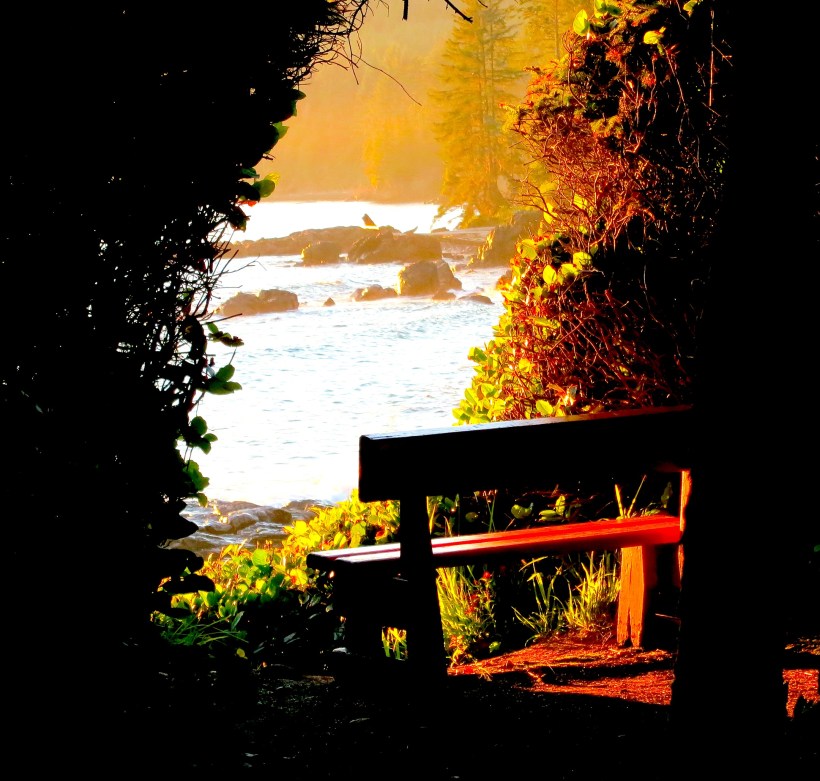

Come sit beside me on my mourning bench.

~Nicholas Wolterstorff from Lament for a Son

I wondered if 7:30 AM was too early to call her. As a sleep-deprived fourth year medical student finishing a long night admitting patients in the hospital, I selfishly needed to hear her voice.

I wanted to know how Margy was doing with the latest round of chemotherapy for breast cancer; I knew she was not sleeping well these days. She was wearing a new halo brace—a metal contraption that wrapped around her head like a scaffolding to secure her degenerating cervical spine from collapsing from metastatic tumor growths in her bones.

She knew, we all knew, she was trying to buy more time from a life of rapidly diminishing days.

Each patient I had seen the previous 24 hours while working in the Emergency Room benefited from the interviewing skills Margy had taught each medical student in our class. She reminded us that each patient had an important story to tell, and no matter how pressured our time, we needed to ask questions that gave permission for that story to be told. As a former nun now married with two teenage children, Margy had become our de facto therapist at a time no medical school hired supportive counselors.

She insisted physicians-in-training remember the suffering soul thriving inside the broken body.

“Just let the patient know with certainty, through your eyes, your body language, your words, that you want to hear what they have to say. You can heal so much hurt simply by sitting beside them and caring enough to listen…”

After her diagnosis with stage 4 cancer, Margy herself became the broken vessel who needed the glue of a good listener. She continued to teach, often from her bed at home. I planned to visit her that day, maybe help out by cleaning her house, or take her for a drive as a diversion.

Her phone rang only once after I dialed her number. There was a long pause; I could hear a clearing of her throat. A deep dam of tears welled behind a muffled “Hello?”

“Margy?”

“Yes? Emily? ”

“Margy? What is it? What’s wrong?”

Her voice shattered like glass into fragments, strangling on words that struggled to form.

“Gordy’s gone, Emily. He’s gone. He’s gone forever…”

“What? What are you saying?”

“A policeman just left. He told us our boy is dead.”

I sat in stunned silence, listening to her sobs, completely unequipped to know how to respond.

None of this made sense. I knew her son was on college spring break, heading to Mexico for a missions trip.

“I’m here, what’s happened?”

“The doorbell rang about an hour ago. Larry got up to answer it. I heard him talking to someone downstairs, so I decided to try to get up and go see what was going on. There was a policeman sitting with Larry on the couch. I knew it had to be about Gordy.”

She paused and took in a shuddering breath.

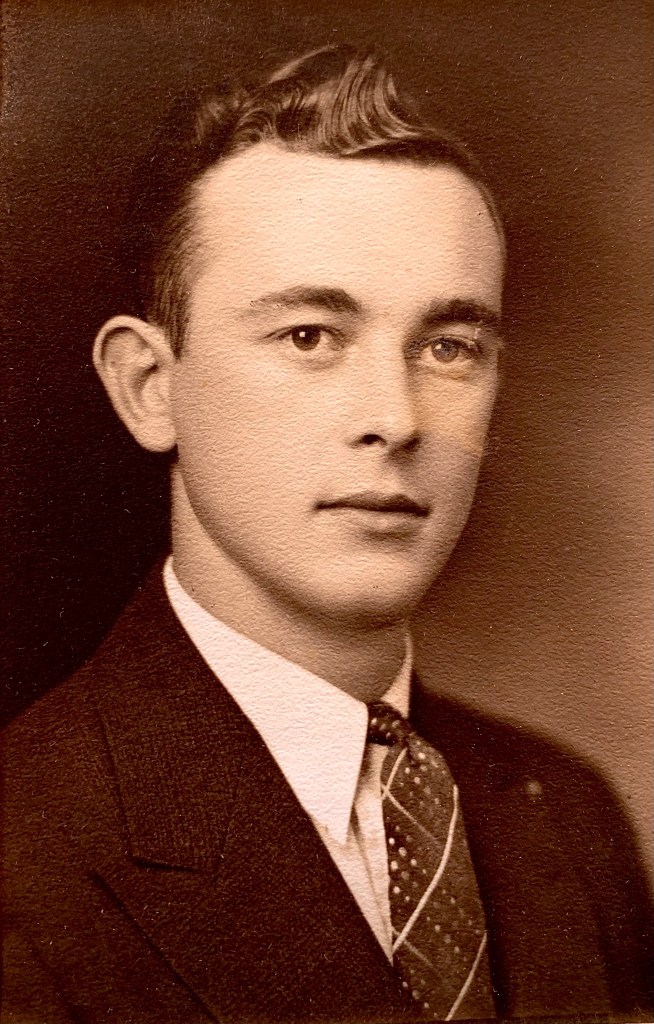

“The group was driving through the night in California. He was asleep in the back of the camper. They think he was sleepwalking and walked right out of the back of the moving camper and was hit by another car.”

Silence. A strangling choking silence.

“They’ll bring him home to me, won’t they? I need to know I can see my boy again. I need to tell him how much I love him.”

“They’ll bring him home to you, Margy.

I’m on my way to help you get ready…“

God is not only the God of the sufferers

but the God who suffers. …

It is said of God that no one can behold his face and live.

I always thought this meant

that no one could see his splendor and live.

A friend said perhaps it meant

that no one could see his sorrow and live.

Or perhaps his sorrow is splendor. …

Instead of explaining our suffering, God shares it.

~Nicholas Wolterstorff from Lament for a Son

This year’s Lenten theme:

…where you go I will go…

Ruth 1:16

Make a one-time or recurring donation to support daily Barnstorming posts

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is deeply appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly