It was hard work, dying, harder

than anything he’d ever done.

Whatever brutal, bruising, back-

Breaking chore he’d forced himself

to endure—it was nothing

compared to this. And it took

so long. When would the job

be over? Who would call him

home for supper? And it was

hard for us (his children)—

all of our lives we’d heard

my mother telling us to go out,

help your father, but this

was work we could not do.

He was way out beyond us,

in a field we could not reach.

~Joyce Sutphen, “My Father, Dying” from Carrying Water to the Field: New and Selected Poems.

We will grieve not, rather find

Strength in what remains behind;

In the primal sympathy

Which having been must ever be;

Thanks to the human heart by which we live,

Thanks to its tenderness, its joys, and fears,

To me the meanest flower that blows can give

Thoughts that do often lie too deep for tears.

~William Wordsworth from “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood”

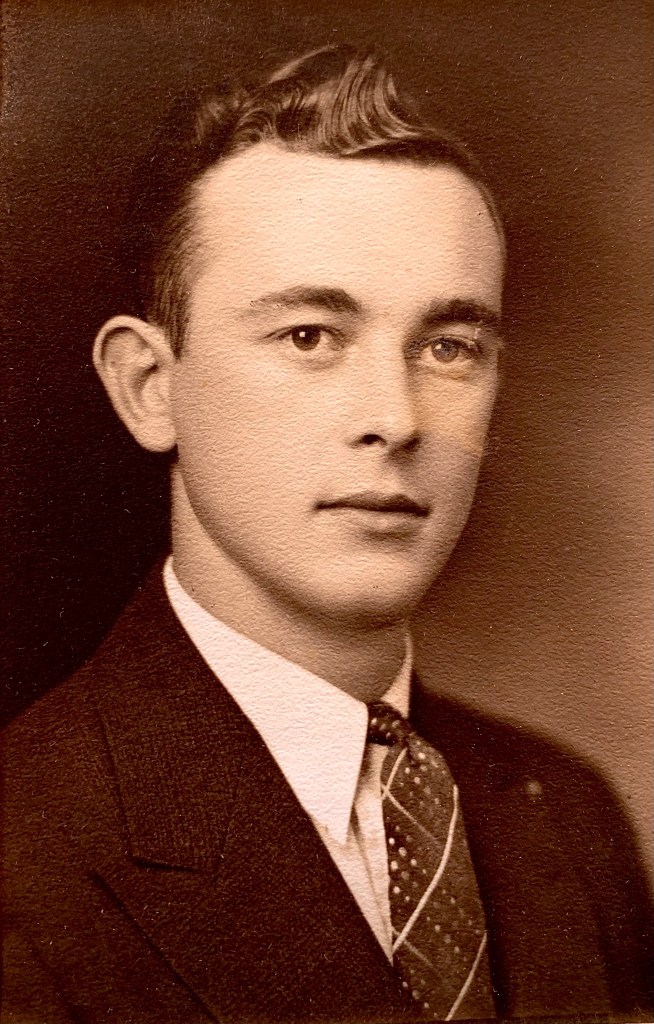

Twenty-six years ago today

we watched at your bedside as you labored,

readying yourself to die and we could not help

except to be there while we watched you

move farther away from us.

This dying, the hardest work you had ever done:

harder than handling the plow behind a team of draft horses,

harder than confronting a broken, alcoholic and abusive father,

harder than slashing brambles and branches to clear the woods,

harder than digging out stumps, cementing foundations, building roofs,

harder than shipping out, leaving behind a new wife after a week of marriage,

harder than leading a battalion of men to battle on Saipan, Tinian and Tarawa,

harder than returning home so changed there were no words,

harder than returning to school, working long hours to support family,

harder than running a farm with only muscle and will power,

harder than coping with an ill wife, infertility, job conflict, discontent,

harder than building your own pool, your own garage, your own house,

harder than your marriage ending, a second wife dying,

and returning home forgiven.

Dying was the hardest of all

as no amount of muscle or smarts could stop it crushing you,

taking away the strength you relied on for 73 years.

So as you lay helpless, moaning, struggling to breathe,

we knew your hard work was complete

and what was yet undone was up to us

to finish for you.

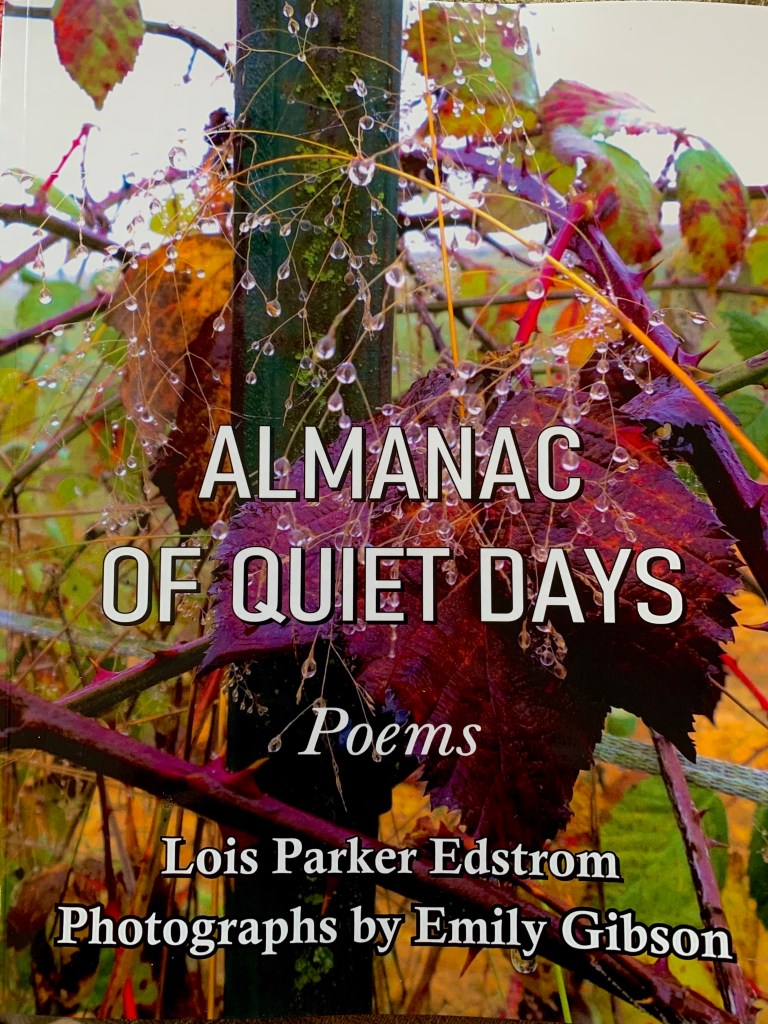

A new book from Barnstorming is available for order here: