Let me say finally, that in the midst of the hollering and in the midst of the discourtesy tonight, we got to come to see that however much we dislike it, the destinies of white and black America are tied together. Now the races don’t understand this apparently. But our destinies are tied together. And somehow, we must all learn to live together as brothers in this country or we’re all going to perish together as fools.

…Whether we like it or not culturally and otherwise, every white person is a little bit negro and every negro is a little bit white. Our language, our music, our material prosperity and even our food are an amalgam of black and white, so there can be no separate black path to power and fulfillment that does not intersect white routes and there can ultimately be no separate white path to power and fulfillment short of social disaster without recognizing the necessity of sharing that power with black aspirations for freedom and human dignity.

~Martin Luther King, Jr.

in one of his last speeches, given at Grosse Point, Michigan high school (near Detroit) to a mostly white and often heckling audience, March 14, 1968

I grew up during the 1960’s in Olympia, Washington, a fair-sized state capitol of 20,000+ people at the time and our city had only one black family.

One.

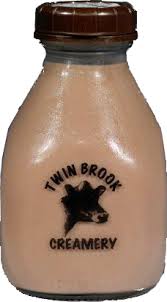

There were a few Japanese and Korean families, a few Hispanics, but other than the Native American folks from the nearby Nisqually Reservation, our community seemed comprised of homogenized milk. Pretty much plain Anglo Saxon white.

In 1970, a white Olympia High School graduation student speaker caused a controversy when she called our town a “white racist ghetto” in her speech. Numerous parents walked out of the ceremony in protest of her protest, and didn’t watch their children graduate.

It was the first time I’d heard someone other than Martin Luther King, Jr. actually crack a previously unspoken barrier using only words. What she said caused much local consternation and anger, but the ensuing debate in the newspaper Letters to the Editor, around lunch counters at the five and dime, and in the churches and real estate offices made a difference. Olympia, after being called out for bigotry in its hiring practices and housing preferences, began to open its social and political doors to people who weren’t white.

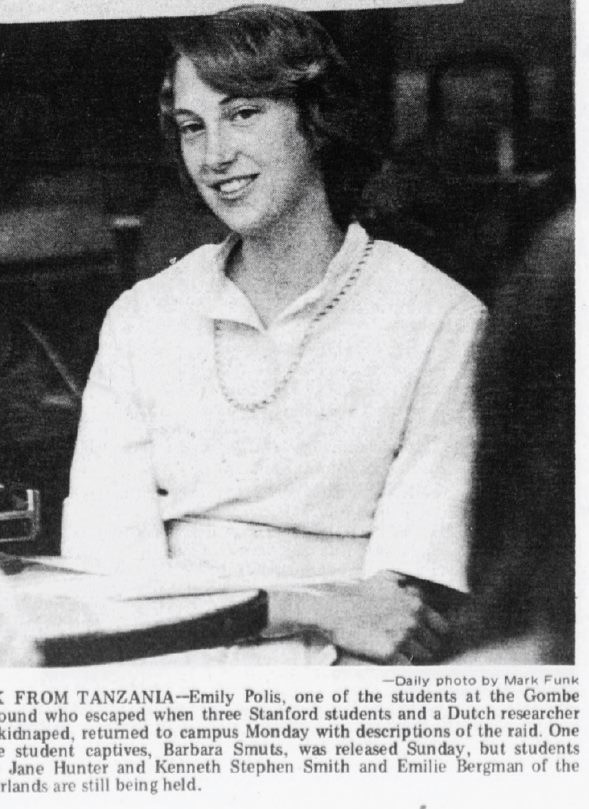

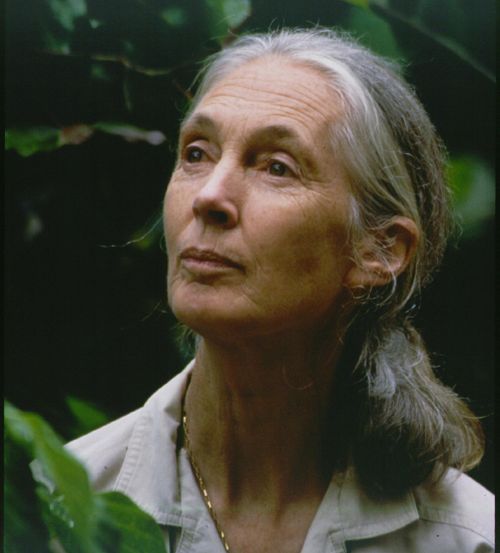

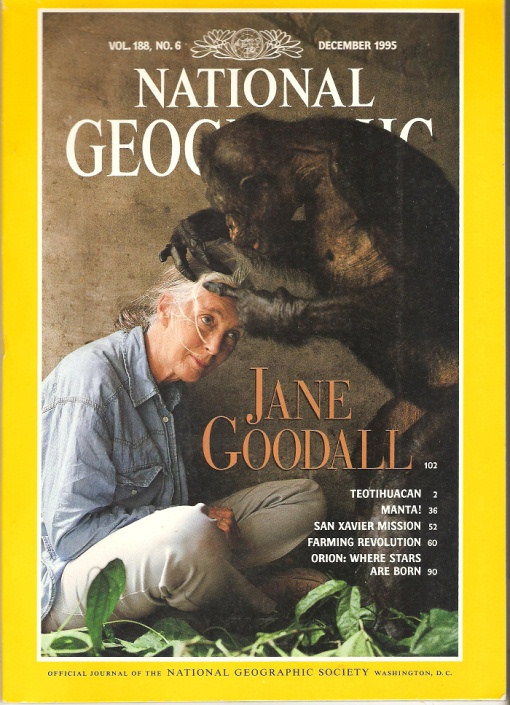

Attending college in California helped broaden my limited point of view, but in the early 70′s there were still few diversity admissions initiatives, so Stanford was still a mostly white campus. While living in Africa to study wild chimpanzees in Africa in 1975, I experienced being one of two whites living and traveling among hundreds of very dark skinned Ugandans, Rwandans, Tanzanians and Kenyans. I became the one gawked at, viewed as an oddity, pointed at by small children who were frightened, amused and perplexed by my appearance.

I constantly felt out of place. I did not belong. Yet I was treated graciously, with hospitality, although always a curiosity: the homogenized white milk in the mix.

There was minimal diversity in my medical school class where women constituted less than 25% of my class graduating in 1980. It wasn’t until I was in family practice residency at Seattle’s Capitol Hill Group Health Cooperative Hospital that I began to experience the world in full technicolor. I joined a group of doctors in training that included an African American activist from the east coast, a Kiowa Indian, several of Jewish background, a son of Mexican immigrants, a daughter of Chinese immigrants, a Japanese American, someone of Spanish descent, and a Yupik Eskimo. I was challenged to appreciate my inner city patients’ cultural, racial, religious, ethnic and sexual minority identities, and saw how much more effectively my colleagues and teachers of diverse backgrounds worked with patients who looked or grew up like them.

My training was such a foundational experience that I was drawn to a medical practice in a Group Health Rainier Valley neighborhood clinic. There I saw patients who lived in the projects that lined Martin Luther King Way, struggling to overcome poverty and social fragmentation, clustered together in knots of extended family within a few square miles. There were many ethnic groups: African Americans, Vietnamese, Cambodian and Laotian refugees, Ashkenazi Jews, Middle East Muslims, Russian immigrants and some Catholic Italian families who spoke broken English. I delivered babies who would grow up learning languages and traditions from every corner of the globe. It was a wide world of diversity walking into my exam rooms, richly filling in the white corners of my life in ways I had never imagined.

I found that white milk, nurturing as it was, was not a reflection of everything the world had to offer.

When I married and Dan and I started our own family, we made the decision to move north near his parents and home community of Lynden, a town of Dutch dairy farming immigrants. We planned to own our own farm to raise our children in a rural setting just as both of us had been raised. There was significant adjustment necessary once again adapting to a primarily Caucasian community. I am not Dutch even though I am as white and tall as the Frieslanders (some of my ancestry is from Schleswig-Holstein in Germany, right across the Holland border). Even though I looked like my neighbors, I still didn’t belong.

I didn’t share the same cultural or church background to fit in easily in my new home. The color of my skin no longer set me apart, but the difference in rituals, language quirks and traditions became very apparent. In other words, the milk looked just as white, (maybe skim versus whole or 2%), but varied significantly in taste (were the cows just let out on grass??)

Over the past thirty plus years since we moved here, our rural community is transforming slowly. We have two growing Native American sovereign nations within a few miles of our farm, the Nooksack and Lummi tribes, along with increasing numbers of migrant Hispanic families who work the seasonal berry and orchard harvest, many of whom have settled in year round. My supervisors at the University where I work are African American. Our close proximity to the lower mainland of British Columbia has brought Taiwanese, Japanese and Hong Kong immigrants to our area, and many East Indians immigrate to our county in large extended families, attracted by affordable farmland. A rural corner grocery close to our farm is owned by Sikhs with shelves stocked with the most amazing array of Indian spices and Mexican chili sauce, with Dutch peppermints and licorice thrown in for good measure.

Our children grew up rural but, as adults, have become part of communities even more varied. Nate teaches multiracial students from a dozen different countries in an international high school in Tokyo, has married a Japanese woman and our beloved granddaughter is biracial. Ben finished two years as a Teach for America high school math teacher on the Pine Ridge Lakota Sioux Reservation in South Dakota, and married to Hilary, have lived as a racial minority in a mostly black neighborhood in New Haven, Connecticut before moving to the melting pot of the Bay Area in California. Lea is teaching fourth graders of multiple ethnicities in a Title 1 school in a military town just a few hours away.

Our children are privileged to work within the kaleidoscope of humanity and our family is blessed to no longer be just plain white milk.

Homogenized means more than just uniformity. It is a unity of substance, a breaking down of barriers so there is no longer obvious separation. Martin Luther King, Jr. called it amalgam — a mixture that yields something stronger than the original parts.

I am still all white on the outside — that I would never want to change — but I can strive to break down barriers that separate me from the diverse people who live, work and worship around me. Thanks to that amalgam, my life is enriched and the flavor of my days remarkably enhanced.