The thing is

to love life, to love it even

when you have no stomach for it

and everything you’ve held dear

crumbles like burnt paper in your hands,

your throat filled with the silt of it.

When grief sits with you, its tropical heat

thickening the air, heavy as water

more fit for gills than lungs;

when grief weights you like your own flesh

only more of it, an obesity of grief,

you think, How can a body withstand this?

Then you hold life like a face

between your palms, a plain face,

no charming smile, no violet eyes,

and you say, yes, I will take you

I will love you, again.

~Ellen Bass, “The Thing Is” from Mules of Love

...everything here

seems to need us

—Rainer Maria Rilke

It’s a hard time to be human. We know too much

and too little. Does the breeze need us?

If you’ve managed to do one good thing,

the ocean doesn’t care.

But when Newton’s apple fell toward the earth,

the earth, ever so slightly, fell

toward the apple.

~Ellen Bass from “The World Has Need of You” from Like a Beggar

Fallen leaves will climb back into trees.

Shards of the shattered vase will rise

and reassemble on the table.

Plastic raincoats will refold

into their flat envelopes. The egg,

bald yolk and its transparent halo,

slide back in the thin, calcium shell.

Curses will pour back into mouths,

letters un-write themselves, words

siphoned up into the pen. My gray hair

will darken and become the feathers

of a black swan. Bullets will snap

back into their chambers, the powder

tamped tight in brass casings. Borders

will disappear from maps. Rust

revert to oxygen and time. The fire

return to the log, the log to the tree,

the white root curled up

in the un-split seed. Birdsong will fly

into the lark’s lungs, answers

become questions again.

When you return, sweaters will unravel

and wool grow on the sheep.

Rock will go home to mountain, gold

to vein. Wine crushed into the grape,

oil pressed into the olive. Silk reeled in

to the spider’s belly. Night moths

tucked close into cocoons, ink drained

from the indigo tattoo. Diamonds

will be returned to coal, coal

to rotting ferns, rain to clouds, light

to stars sucked back and back

into one timeless point, the way it was

before the world was born,

that fresh, that whole, nothing

broken, nothing torn apart.

~Ellen Bass “When You Return” from Like a Beggar

There is so much grief these days

so much anger,

so much loss of life,

so much weeping.

How can we withstand this?

How can we know, now,

when we are barely able to breathe

that we might know – at some point –

we might have the stomach to love life again?

This time of year, no matter which way I turn, autumn’s kaleidoscope displays new patterns, new colors, new empty spaces as I watch the world die into itself once again.

Some dying is flashy, brilliant, blazing – a calling out for attention. Then there is the hidden dying that happens without anyone taking notice: just a plain, tired, rusting away letting go.

I spent this morning adjusting to the change in season by occupying myself with the familiar task of moving manure. Cleaning barn is a comforting chore, allowing me to transform tangible benefit from something objectionable and just plain stinky to the nurturing fertilizer of the future.

It feels like I’ve actually accomplished something.

As I scoop and push the wheelbarrow, I recalled another barn cleaning 24 years ago, just days before the world changed on 9/11/01.

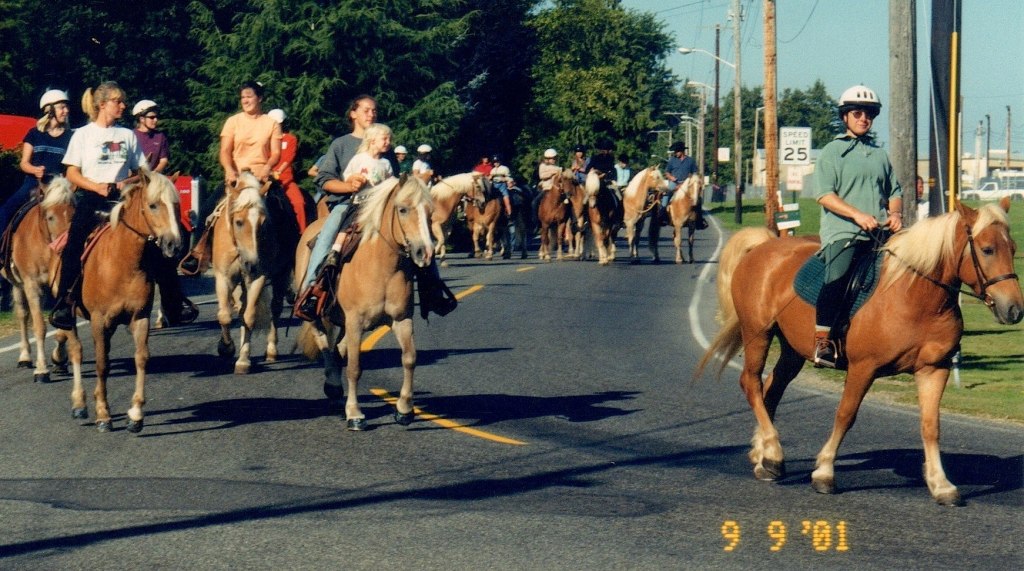

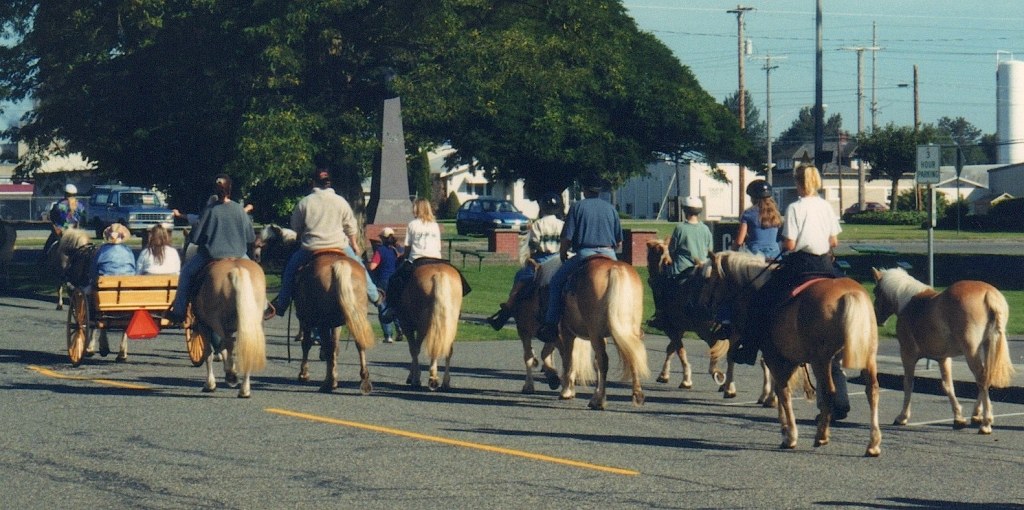

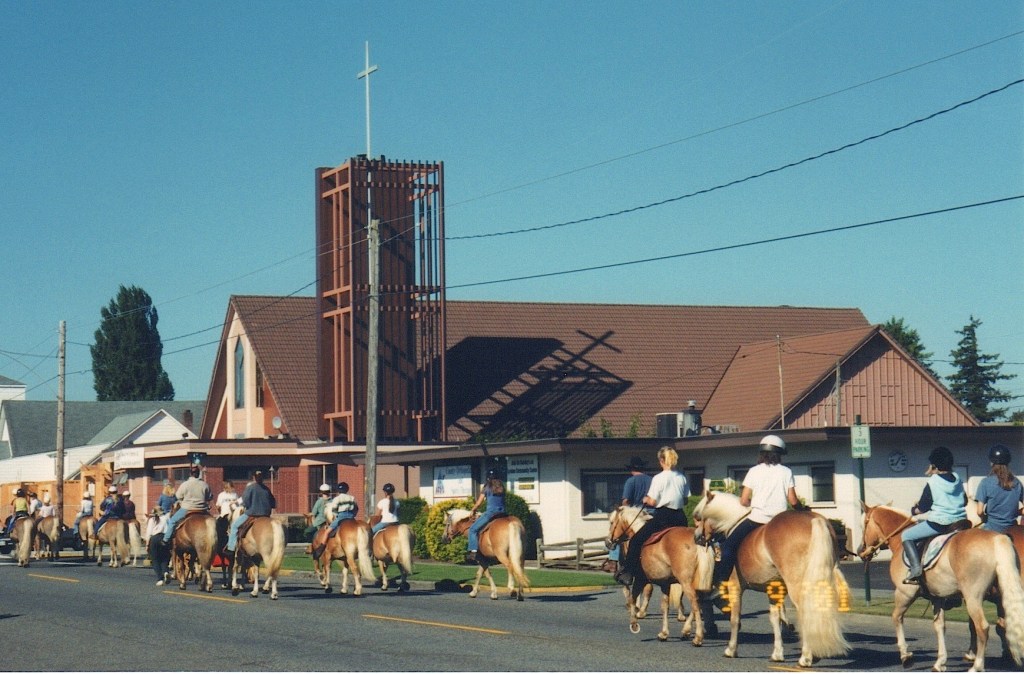

I was one of three or four friends left cleaning over ninety stalls after a Haflinger horse event that I had organized at our local fairgrounds. Some people had brought their horses from over 1000 miles away to participate for several days, including a Haflinger parade through our town on a quiet Sunday morning.

There had been personality clashes and harsh words among some participants along with criticism directed at me as the organizer that I had taken very personally. As I struggled with the umpteenth wheelbarrow load of manure, tears stung my eyes and my heart.

I was miserable with regret, feeling my work had been futile and unappreciated.

One friend had stayed behind with her young family to help clean up the large facility and she could see I was struggling to keep my composure. Jenny put herself right in front of my wheelbarrow and looked me in the eye, insisting I stop for a moment and listen:

“You know, none of these troubles and conflicts will amount to a hill of beans years from now. People will remember a fun event in a beautiful part of the country, a wonderful time with their Haflingers, their friends and family, and they’ll be all nostalgic about it, not giving a thought to the infighting or the sour attitudes or who said what to whom. So don’t make this about you and whether you did or didn’t make everyone happy. You loved us all enough to make it possible to meet here and the rest was up to us. So quit being upset about what you can’t change. There’s too much you can still do for us.”

Jenny had no idea how wise her words were, even two days later, on 9/11.

During tough times since (and there have been plenty), Jenny’s advice replays, reminding me to cease seeking appreciation from others or feeling hurt when harsh words come my way.

She was right about the balm found in the tincture of time. She was right about giving up the upset in order to die to self and self absorption, and instead to focus outward.

I have remembered.

Jenny herself did not know that day she would subsequently spend six years dying while still loving life every day, fighting a relentless cancer that was only slowed in the face of her faith and intense drive to live.

She became a rusting leaf gone holy, fading imperceptibly over time, crumbling at the edges until she finally had to let go. Her dying did not flash brilliance, nor draw attention at the end. Her intense focus during the years of her illness had always been outward to others, to her family and friends, to the healers she spent so much time with in medical offices, to her firm belief in the plan God had written for her and those who loved her.

So Jenny let go her hold on life here. And we reluctantly let her go. Brilliance cloaks her as her focus is now on things eternal.

You were so right, Jenny. The hard feelings from a quarter century ago don’t amount to a hill of beans now. The words you spoke to me that day taught me to love life even when I have no stomach for it.

All of us did have a great time together a few days before the world changed. And manure transforms over time to rich, nurturing compost.

I promise I am no longer upset that I can’t change what is past nor the fact that you and so many others have now left us.

But we’ll catch up later.

Make a one-time or recurring donation to support daily Barnstorming posts

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is deeply appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly