In the quiet misty morning

When the moon has gone to bed,

When the sparrows stop their singing

And the sky is clear and red,

When the summer’s ceased its gleaming

When the corn is past its prime,

When adventure’s lost its meaning –

I’ll be homeward bound in time

Bind me not to the pasture

Chain me not to the plow

Set me free to find my calling

And I’ll return to you somehow

If you find it’s me you’re missing

If you’re hoping I’ll return,

To your thoughts I’ll soon be listening,

And in the road I’ll stop and turn

Then the wind will set me racing

As my journey nears its end

And the path I’ll be retracing

When I’m homeward bound again

Bind me not to the pasture

Chain me not to the plow

Set me free to find my calling

And I’ll return to you somehow

In the quiet misty morning

When the moon has gone to bed,

When the sparrows stop their singing

I’ll be homeward bound again.

~Marta Keen “Homeward Bound”

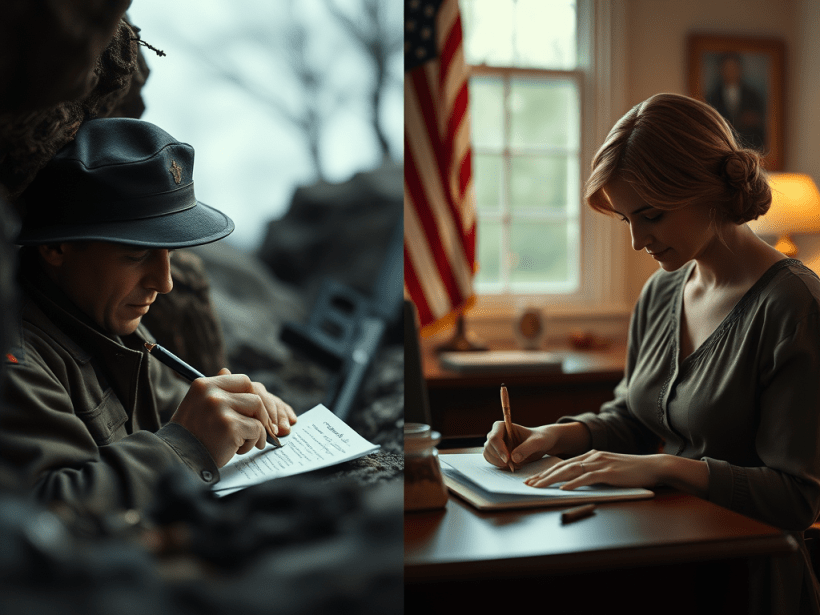

Eighty-two years ago, my parents married on Christmas Eve. It was not a conventional wedding day but a date of necessity, only because a justice of the peace was available to marry a score of war-time couples in Quantico, Virginia, shortly before the newly trained Marine officers were shipped out to the South Pacific to fight in WWII.

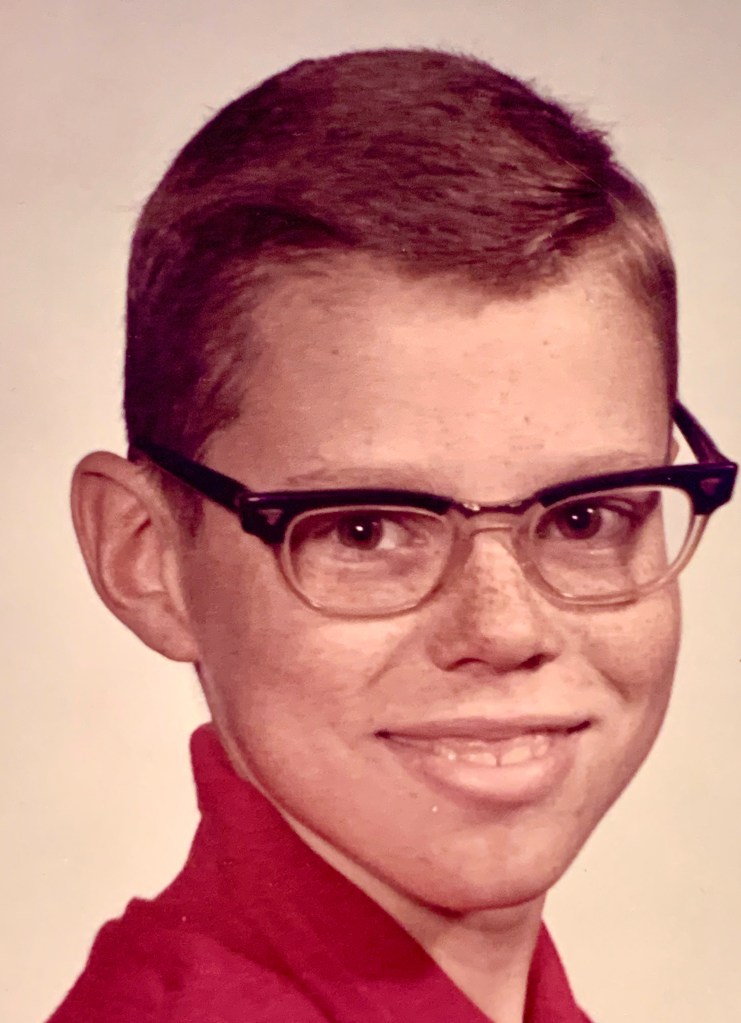

When I look at my parents’ young faces – ages 22 and just turned 21 — in their only wedding portrait, I see a hint of the impulsive decision that led to that wedding just a week before my father left for 30 months. They had known each other at college for over a year, had talked about a future together, but with my mother starting a teaching job in a rural Eastern Washington town, and the war potentially impacting all young men’s lives very directly, they had not set a date.

My father put his college education on hold to enlist, knowing that would give him some options he wouldn’t have if drafted, so they went their separate ways as he headed east to Virginia for his Marine officer training, and Mom started her high school teaching career as a speech and drama teacher. One day in early December of 1942, he called her and said, “If we’re going to get married, it’ll need to be before the end of the year. I’m shipping out the first week in January.” Mom went to her high school principal, asked for a two week leave of absence which was granted, told her astonished parents, bought a dress, and headed east on the train with a friend who had received a similar call from her boyfriend.

This was a completely uncharacteristic thing for my overly cautious mother to do, so… it must have been love.

They were married in a brief civil ceremony with another couple as the witnesses. They stayed in Virginia only a couple days and took the train back to San Diego, and my father was shipped out. Just like that. Mom returned to her teaching position and the first three years of their married life was composed of letter correspondence only, with gaps of up to a month during certain island battles when no mail could be delivered or posted.

As I sorted through my mother’s things following her death over a decade ago, I found their war-time letters to each other, stacked neatly and tied together in a box.

In my father’s nearly daily letters home to my mother during WWII, month after month after month, he would say, over and over, while apologizing for the repetition:

“I will come home to you, I will return, I will not let this change me, we will be joined again…”

This was his way of convincing himself even as he carried the dead and dying after island battles: men he knew well and the enemy he did not know. He knew they were never returning to the home they died protecting and to those who loved them.

He shared little of battle in his letters as each letter was reviewed and signed off by a censor before being sealed and sent. This story, however, made it through:

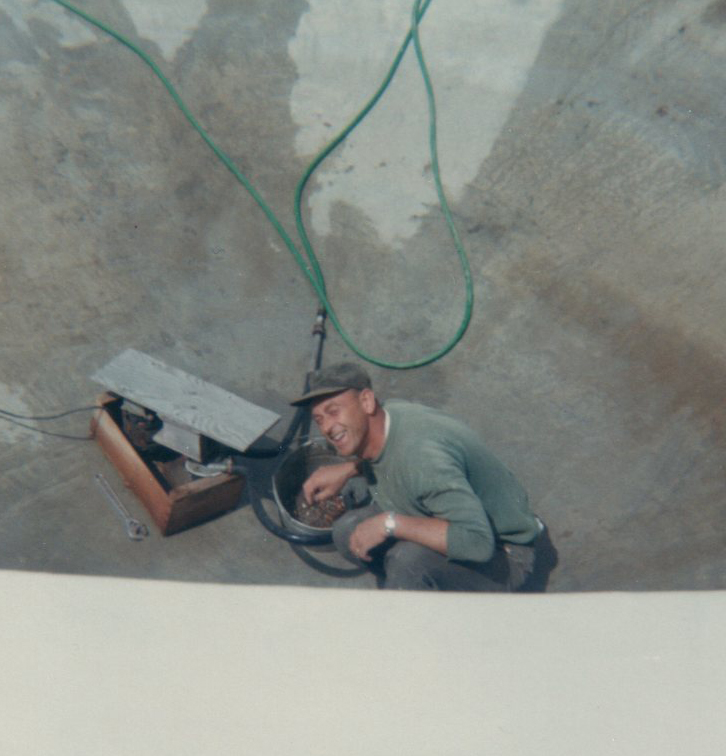

“You mentioned a story of Navy landing craft taking the Marines into Tarawa. It reminded me of something which impressed me a great deal and something I’m sure I’ll never forget.

So you’ll understand what I mean I’ll try to start with an explanation. In training – close order drill- etc. there is a command that is given always when the men form in the morning – various times during the day– after firing– and always before a formation is dismissed. The command is INSPECTION – ARMS. On the command of EXECUTION- ARMS each man opens the bolt of his rifle. It is supposed to be done in unison so you hear just one sound as the bolts are opened. Usually it is pretty good and sounds O.K.

Just to show you how the morale of the men going to the beach was – and how much it impressed me — we were on our way in – I was forward, watching the beach thru a little slit in the ramp – the men were crouched in the bottom of the boat, just waiting. You see- we enter the landing boats with unloaded rifles and wait till it’s advisable before loading. When we got about to the right distance in my estimation I turned around and said – LOAD and LOCK – I didn’t realize it, but every man had been crouching with his hand on the operating handle and when I said that — SLAM! — every bolt was open at once – I’ve never heard it done better – and those men meant business when they loaded those rifles.

A man couldn’t be afraid with men like that behind him.”

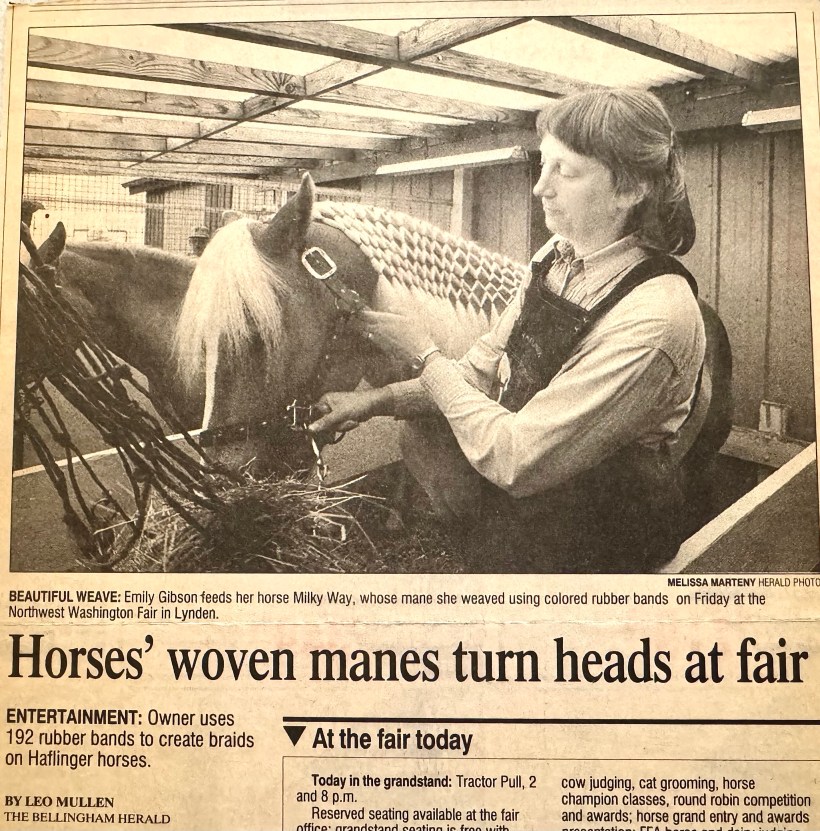

My father did return home to my mother after nearly three years of separation. He finished his college education to become an agriculture teacher to teach others how to farm the land while he himself became bound to the pasture and chained to the plow.

He never forgot those who died, making it possible for him to return home. I won’t forget either.

My mother and father could not have foretold the struggles that lay ahead for them. The War itself seemed struggle enough for the millions of couples who endured the separation, the losses and grieving, as well as the eventual injuries–both physical and psychological. It did not seem possible that beyond those harsh and horrible realities, things could go sour after reuniting.

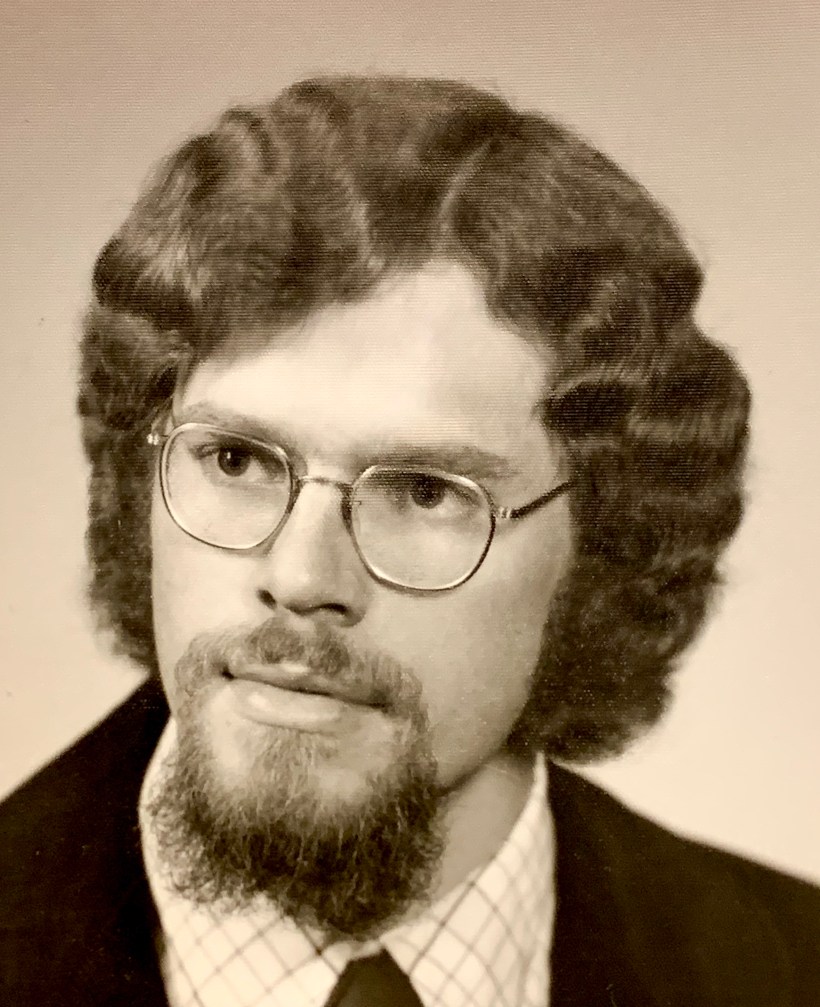

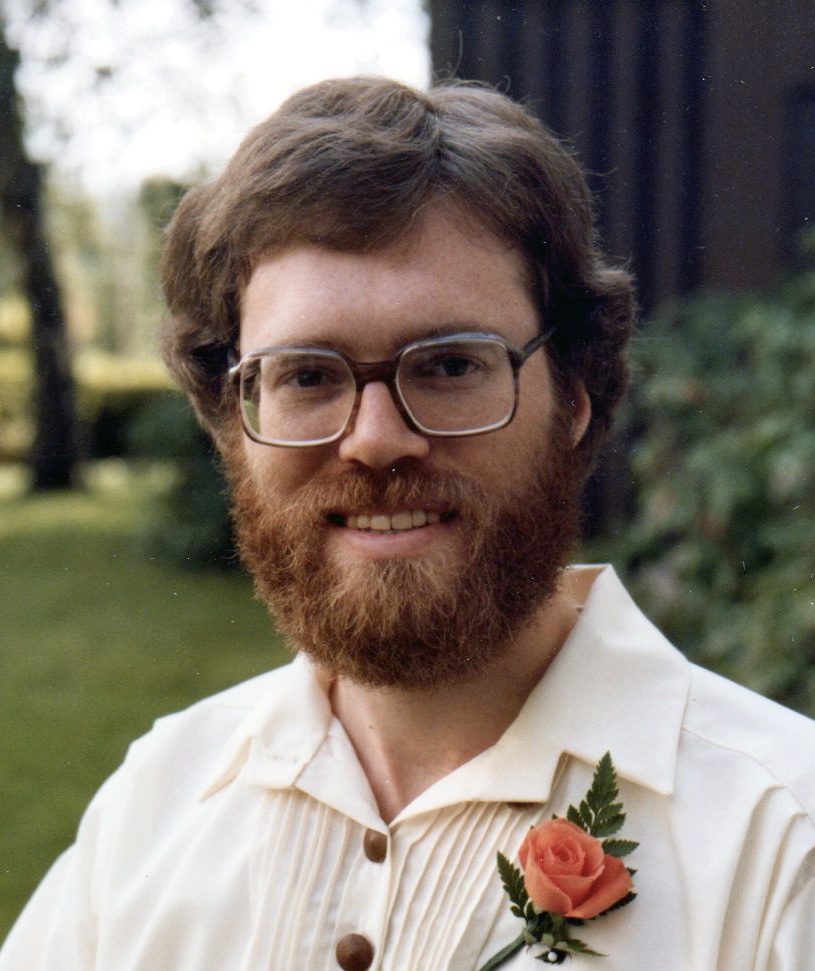

The hope and expectation of happiness and bliss must have been overwhelming, and real life doesn’t often deliver. After raising three children, their 35 year marriage fell apart with traumatic finality. When my father returned home (again) over a decade later, asking for forgiveness, they remarried and had five more years together before my father died in 1995.

Christmas is a time of joy, a celebration of new beginnings and new life when God became man, humble, vulnerable and tender. But it also gives us a foretaste for the profound sacrifice made in giving up this earthly life, not always so gently.

As I peer at my father’s and mother’s faces in their wedding photo, I remember those eyes, then so trusting and unaware of what was to come. I find peace in knowing they both have returned home to behold the Light, the Salvation and the Glory~~the ultimate Christmas~~in His presence.

Make a one-time or recurring donation to support daily Barnstorming posts

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is deeply appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly