… The Amish have maintained what I like to think is a proper scale, largely by staying with the horse. The horse has restricted unlimited expansion.

Not only does working with horses limit farm size, but horses are ideally suited to family life.

With horses you unhitch at noon to water and feed the teams and then the family eats what we still call dinner. While the teams rest there is usually time for a short nap.

And because God didn’t create the horse with headlights,

we don’t work nights.

~Amish farmer David Kline in Great Possessions

You can’t have the family farm without the family.

~G.K. Chesterton from “The Unprecedented Architecture of Commander Blair,” Tales of the Long Bow

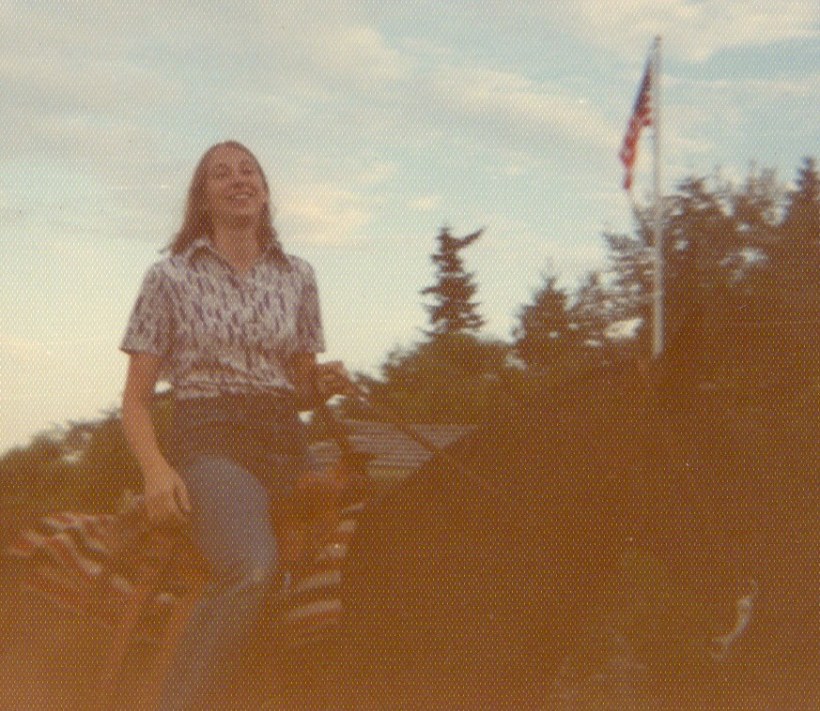

I’m 71 years old ~ old enough to have parents who grew up on farms worked by horses, one raising wheat and lentils in the Palouse country of eastern Washington and the other logging in the woodlands of Fidalgo Island of western Washington. The horses were crucial to my grandfathers’ success in caring for and tilling the land, seeding and harvesting the crops and bringing supplies from town miles away. Theirs was a hardscrabble life in the early 20th century with few conveniences. Work was year round from dawn to dusk; caring for the animals came before any human comforts. Once night fell, work ceased and sleep was welcome respite for man and beast.

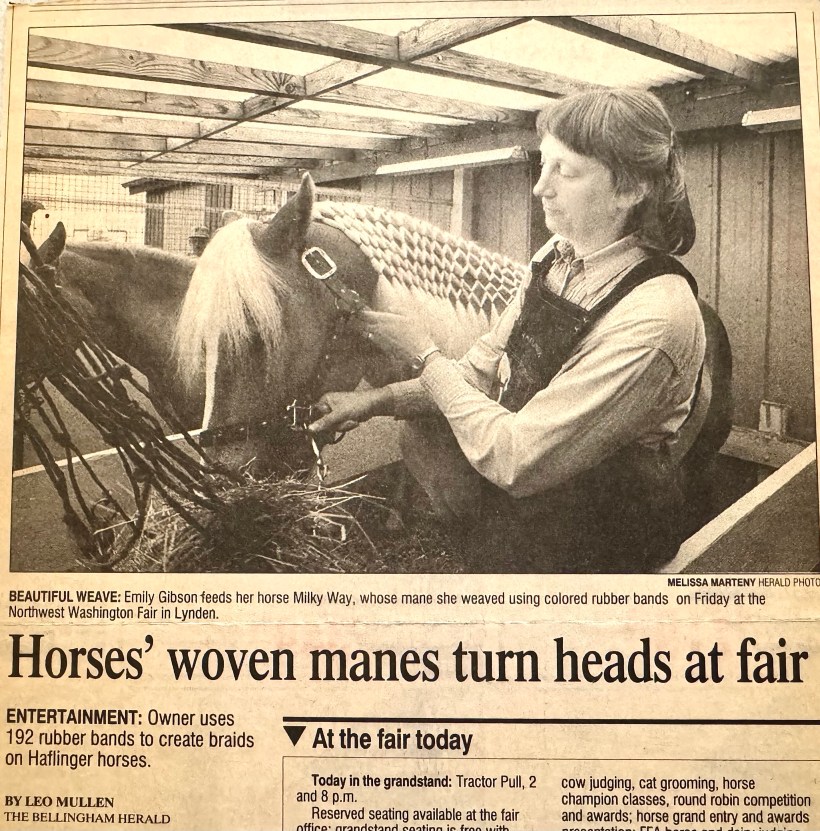

In the rural NW Washington countryside where we live, we’ve been fortunate enough to live near farmers who still dabble in horse farming, whose draft teams are hitched to plows and mowers and manure spreaders as they head out to the fields to recapture the past. They still gather together in the spring to have a well-attended and friendly competition plowing match.

Watching a good team work with no diesel motor running means hearing bird calls from the field, the steady footfall of the horses, the harness chains jingling, the leather straps creaking, the machinery shushing quietly as gears turn and grass lays over in submission. No ear protection is needed. There is no clock needed to pace the day.

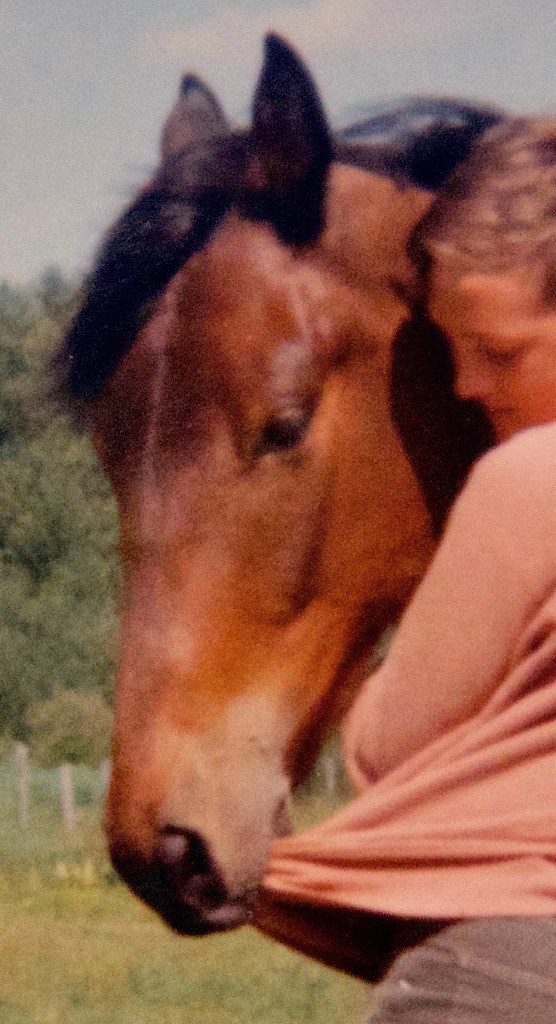

There is a rhythm of nurture when animals instead of engines are part of the work day. The gauge for taking a break is the amount of foamy sweat on the horses and how fast they are breathing.

It is time to stop and take a breather,

it is time to start back up to do a few more rows,

it is time to water,

it is time for a meal,

it is time for a nap,

it is time for a rest in a shady spot.

This is gentle use of the land with four footed stewards who deposit right back to the soil the digested forage they have eaten only hours before.

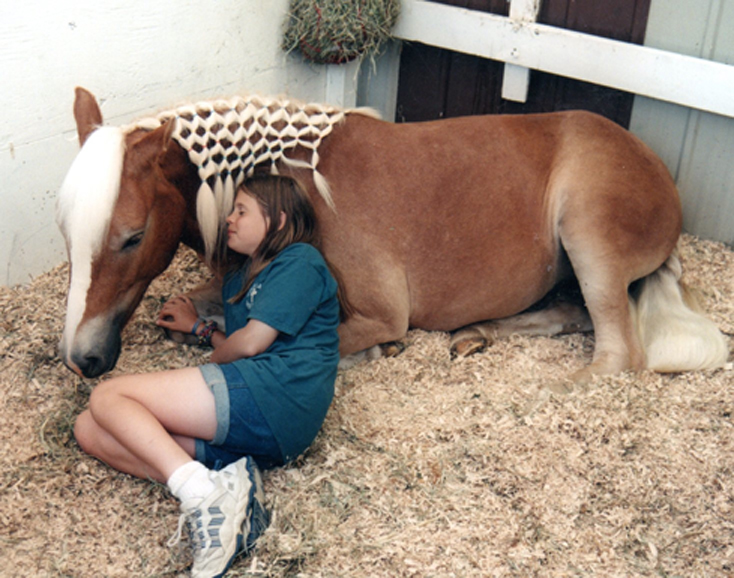

Our modern fossil-fuel-powered approach to food production has bypassed the small family farm which was so dependent on the muscle power of humans and animals. In our move away from horses worked by skilled teamsters, what has been gained in high production values has meant loss of self-sufficiency and dedicated stewardship of a smaller acreage. Draft breeds, including the Haflinger horses we raised for forty years, now are bred for higher energy with lighter refined bone structure meant more for eye appeal and floating movement, rather than the sturdy conformation and unflappable low maintenance mindset needed for pulling work.

Modern children grow up with a different set of values as well, no longer raised to work together with other family members, as well as the animals on the farm for a common purpose of daily survival.

Still fascinated by the The Small Farmer’s Journal, I am encouraged when the next generation reaches for horse collars and bridles, hitches up their horses to do the work as it used to be done. Although the modern world will never go back to the days of horse-drawn farming and transportation, we can acknowledge there were some benefits to the old ways of doing things, when progress meant being harnessed together as a team with our horses, tilling for truth and harvesting hope.

I like farming. I like the work.

I like the livestock and the pastures and the woods.

It’s not necessarily a good living, but it’s a good life.

I now suspect that if we work with machines

the world will seem to us to be a machine,

but if we work with living creatures

the world will appear to us as a living creature.

That’s what I’ve spent my life doing,

trying to create an authentic grounds for hope.

~Wendell Berry, horse farmer, essayist, poet, professor

Make a one-time or recurring donation to support daily Barnstorming posts

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is deeply appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly