As a physician-in-training in the late 1970’s, I rotated among a variety of inner city public hospitals, learning clinical skills on patients who were grateful to have someone, anyone, care enough to take care of them. There were plenty of homeless street people who needed to be deloused before the “real” doctors would touch them, and there were the alcoholic diabetics whose gangrenous toes would self-amputate as I removed stinking socks. There were people with gun shot wounds and stabbings who had police officers posted at their doors and rape victims who were beaten and poisoned into submission and silence. Someone needed to touch them with compassion when their need was greatest.

As a 25 year old idealistic and naive student, I truly believed I could make a difference in the 6 weeks I spent in any particular hospital rotation. That proved far too grandiose and unrealistic, yet there were times I did make a difference, sometimes not so positive, in the few minutes I spent with a patient. As part of the training process, mistakes were inevitable. Lungs collapsed when putting in central lines, medications administered caused anaphylactic shock, pain and bleeding caused by spinal taps–each error creates a memory that never will allow such a mistake to occur again. It is the price of training a new doctor and the patient always–always– pays the price.

I was finishing my last on-call night on my obstetrical rotation at a large military hospital that served an army base. The hospital, built during WWII was a series of far flung one story bunker buildings connected by miles of hallways–if one part were bombed, the rest of the hospital could still function. The wing that contained the delivery rooms was factory medicine at its finest: a large ward of 20 beds for laboring and 5 delivery rooms which were often busy all at once, at all hours. Some laboring mothers were married girls in their midteens whose husbands were stationed in the northwest, transplanting their young wives thousands of miles from their families and support systems. Their bittersweet labors haunted me: children delivering babies they had no idea how to begin to parent.

I had delivered 99 babies during my 6 week rotation. My supervising residents and the nurses on shift had kept me busy on that last day trying to get me to the *100th* delivery as a point of pride and bragging rights; I had already followed and delivered 4 women that night and had fallen exhausted into bed in the on call-room at 3 AM with no women currently in labor, hoping for two hours of sleep before getting up for morning rounds. Whether I reached the elusive *100* was immaterial to me at that moment.

I was shaken awake at 4:30 AM by a nurse saying I was needed right away. An 18 year old woman had arrived in labor only 30 minutes before and though it was her first baby, she was already pushing and ready to deliver. My 100th had arrived. The delivery room lights were blinding; I was barely coherent when I greeted this almost-mother and father as she pushed, with the baby’s head crowning. The nurses were bustling about doing all the preparation for the delivery: setting up the heat lamps over the bassinet, getting the specimen pan for the placenta, readying suture materials for the episiotomy.

I noticed there were no actual doctors in the room so asked where the resident on call was.

What? Still in bed? Time to get him up! Delivery was imminent.

I knew the drill. Gown up, gloves on, sit between her propped up legs, stretch the vulva around the crowning head, thinning and stretching it with massaging fingers to try to avoid tears. I injected anesthetic into the perineum and with scissors cut the episiotomy to allow more room, a truly unnecessary but, at the time, standard procedure in all too many deliveries. Amniotic fluid and blood dribbled out then splashed on my shoes and the sweet salty smell permeated everything. I was concentrating so hard on doing every step correctly, I didn’t think to notice whether the baby’s heart beat had been monitored with the doppler, or whether a resident had come into the room yet or not. The head crowned, and as I sucked out the baby’s mouth, I thought its face color looked dusky, so checked quickly for a cord around the neck, thinking it may be tight and compromising. No cord found, so the next push brought the baby out into my lap. Bluish purple, floppy, and not responding. I quickly clamped and cut the cord and rubbed the baby vigorously with a towel.

Nothing, no response, no movement, no breath. Nothing. I rubbed harder.

A nurse swept in and grabbed the baby and ran over to the pediatric heat lamp and bed and started resuscitation.

Chaos ensued. The mother and father began to panic and cry, the pediatric and obstetrical residents came running, hair askew, eyes still sleepy, but suddenly shocked awake with the sight of a blue floppy baby.

I sat stunned, immobilized by what had just happened in the previous five minutes. I tried to review in my foggy mind what had gone wrong and realized at no time had I heard this baby’s heart beat from the time I entered the room. The nurses started answering questions fired at me by the residents, and no one could remember listening to the baby after the first check when they had arrived in active pushing labor some 30 minutes earlier. The heart beat was fine then, and because things happened so quickly, it had not been checked again. It was not an excuse, and it was not acceptable. It was a terrible terrible error. This baby had died sometime in the previous half hour. It was not apparent why until the placenta delivered in a rush of blood and it was obvious it had partially abrupted–prematurely separated from the uterine wall so the circulation to the baby had been compromised. Potentially, with continuous fetal monitoring, this would have been detected and the baby delivered in an emergency C section in time. Or perhaps not. The pediatric resident worked for another 20 minutes on the little lifeless baby.

The parents held each other, sobbing, while I sewed up the episiotomy. I had no idea what to say, mortified and helpless as a witness and perpetrator of such agony. I tried saying I was so sorry, so sad they lost their baby, felt so badly we had not known sooner. There was nothing that could possibly comfort them or relieve their horrible loss or the freshness of their raw grief.

And of course they had no words of comfort for my own anguish.

Later, in another room, my supervising resident made me practice intubating the limp little body so I’d know how to do it on something other than a mannequin. I couldn’t see the vocal cords through my tears but did what I was told, as I always did.

I cried in the bathroom, a sad exhausted selfish weeping. Instead of achieving that “perfect” 100, I learned something far more important: without constant vigilance, and even with it, tragedy intervenes in life unexpectedly without regard to age or status or wishes or desires. I went on as a family physician to deliver a few hundred babies during my career, never forgetting the baby that might have had a chance, if only born at a hospital with adequately trained well rested staff without a med student trying to reach a meaningless goal.

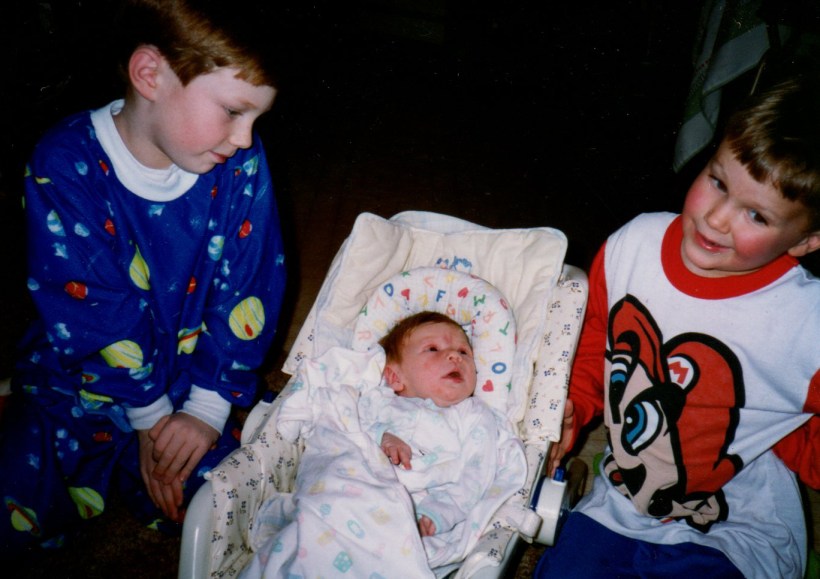

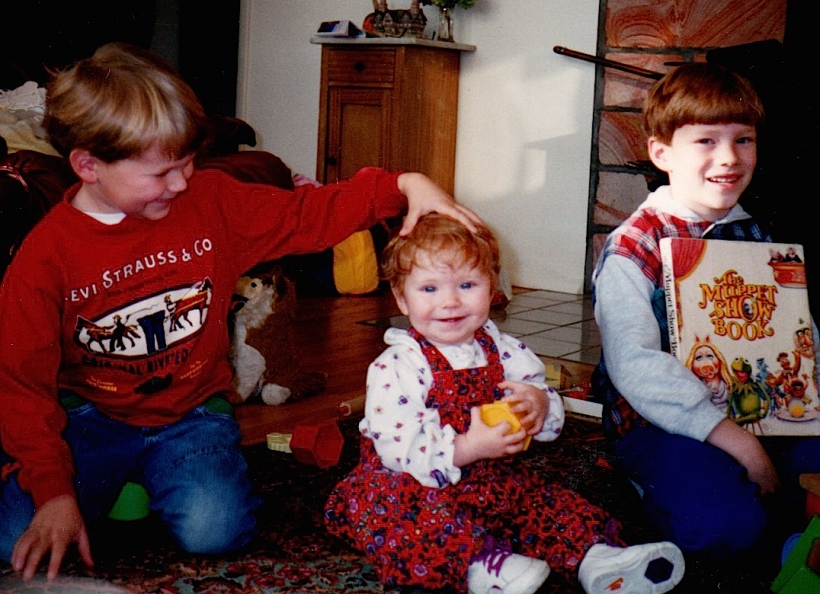

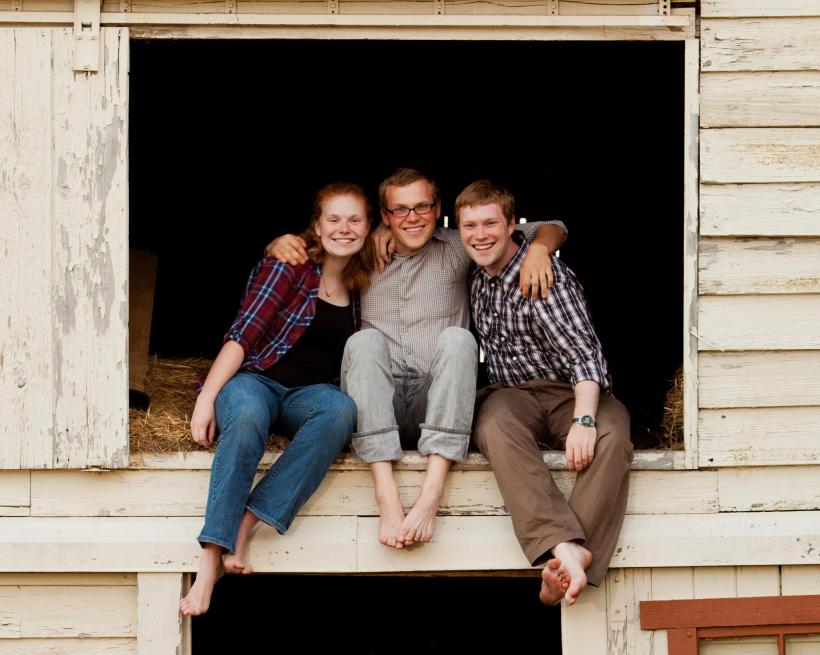

This baby should now be in his 30’s with children of his own, his parents now proud and loving grandparents.

I wonder if I’ll meet him again — this little soul only a few minutes away from a full life — if I’m ever forgiven enough to share a piece of heaven with humanity’s millions of unborn babies who, through intention or negligence, never had opportunity to draw a breath.

Then, just maybe then, forgiveness will feel real and grace will flood the terrible void where, not for the first time nor the last, guilt overwhelmed what innocence I had left.

For more information :

Intrauterine Fetal Demise – birthinjurycenter.org/types-of-birth-injuries/intrauterine-fetal-demise/