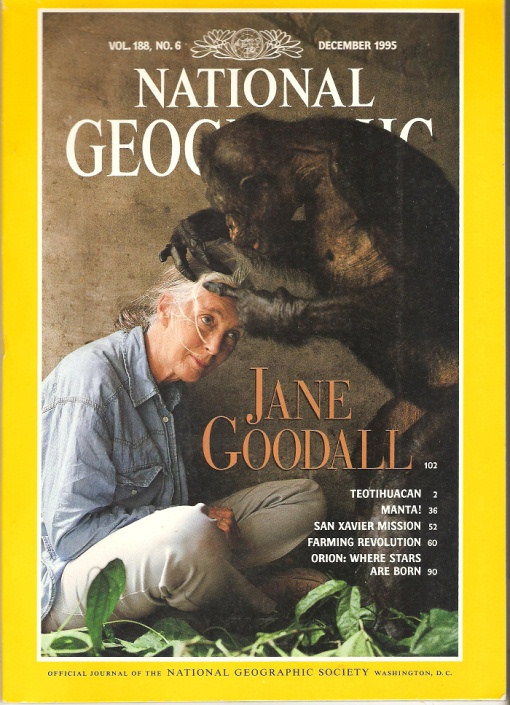

I wasn’t prepared to hear yesterday that my professor, mentor, and friend Dr. Jane Goodall had passed away at age 91, while in the midst of her lecture tour in the United States.

I nearly believed Jane would be immortal; she lived as if she were.

She had a message to deliver and as long as she could, she would. She truly “died in the harness” after decades and decades of traveling the world, recruiting people to her cause to save the world for the next generation of plants, animals and humans, and the next and the next…

She was a born observer and storyteller, able to reach and move us with her verbal and writing ability to help place us in her shoes in the wild as she witnessed what no one else had. This was, of course, aided by Hugo van Lawick’s compelling wildlife photography and video every child of the 1950s and 60s grew up watching.

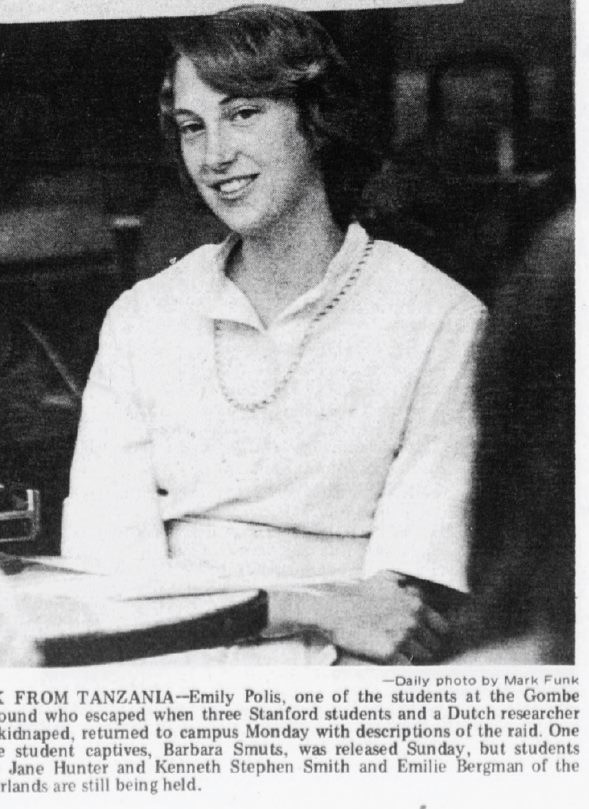

As a college student taking her class on non-human primate behavior, I was riveted by the content of her course lectures about the work she was doing at Gombe. I hoped I could somehow help in the long-term study there, and was ready to commit to a year of training preparation: recording captive chimpanzee behavior at Stanford, while learning Swahili.

On a spring day in May 1974:

Standing outside a non-descript door in a long dark windowless hallway of offices at the Stanford Medical Center, I took a deep breath and swallowed several times to clear my dry throat. I hoped I had found the correct office, as there was only a number– no nameplate to confirm who was inside.

I was about to meet my childhood hero, someone whose every book I’d read and every TV documentary I had watched. I knocked with what I hoped was the right combination of assertiveness (“I want to be here to talk with you and prove my interest”) and humility (“I hope this is a convenient time for you as I don’t want to intrude”).

I heard a soft voice on the other side say “Come in” so I slowly opened the door.

It was a bit like going through the wardrobe to enter Narnia.

Bright sunlight streamed into the dark hallway as I stepped over the threshold. Squinting, I stepped inside and quickly shut the door behind me as I realized there were at least four birds flying about the room. They were taking off and landing, hopping about feeding on bird seed on the office floor and on the window sill. The windows were flung wide open with a spring breeze rustling papers on the desk. The birds were very happy occupying the sparsely furnished room, which contained only one desk, two chairs and Dr. Jane Goodall.

She stood up and extended her hand to me, saying, quite unnecessarily, “Hello, I’m Jane” and offered me the other chair when I told her my name. She was slighter than she appeared when speaking up at a lectern, or on film. Sitting back down at her desk, she busied herself reading and marking her papers, seemingly occupied for a bit and not to be disturbed.

It was as if I was not there at all.

It was disorienting. In the middle of a bustling urban office complex containing nothing resembling plants or a natural environment, I had unexpectedly stepped into a bird sanctuary instead of sitting down for a job interview. I wasn’t sure what I was supposed to do or say. Jane didn’t really ever look directly at me, yet I was clearly being observed.

So I waited, watching the birds making themselves at home in her office, and slowly feeling more at home myself. I felt my tight muscles start to relax and I loosened my grip on the arms of the chair.

There was silence except for the twittering of the finches as they flew about our heads.

Then she spoke, her eyes still perusing papers:

“It really is the only way I can tolerate being here for any length of time. They keep me company. But don’t tell anyone; the people here at the medical center would think this is rather unsanitary.”

I said the only thing I could think of:

“I think it is magical. It reminds me of home.”

Only then did she look at me.

“Now tell me why you’d like to come work at Gombe…”

The next day I received a note from her letting me know I was accepted for the research assistant-ship to begin a year later, once I had completed all aspects of the training.

I had proven I could sit silently and expectantly, waiting for something, or perhaps nothing at all, to happen. For a farm girl who had never before traveled outside the United States, I had stepped through the wardrobe into Jane’s amazing world, about to embark on an adventure far beyond the barnyard.

(This essay was published in The Jane Effect in 2015 in honor of Jane’s 80th birthday)

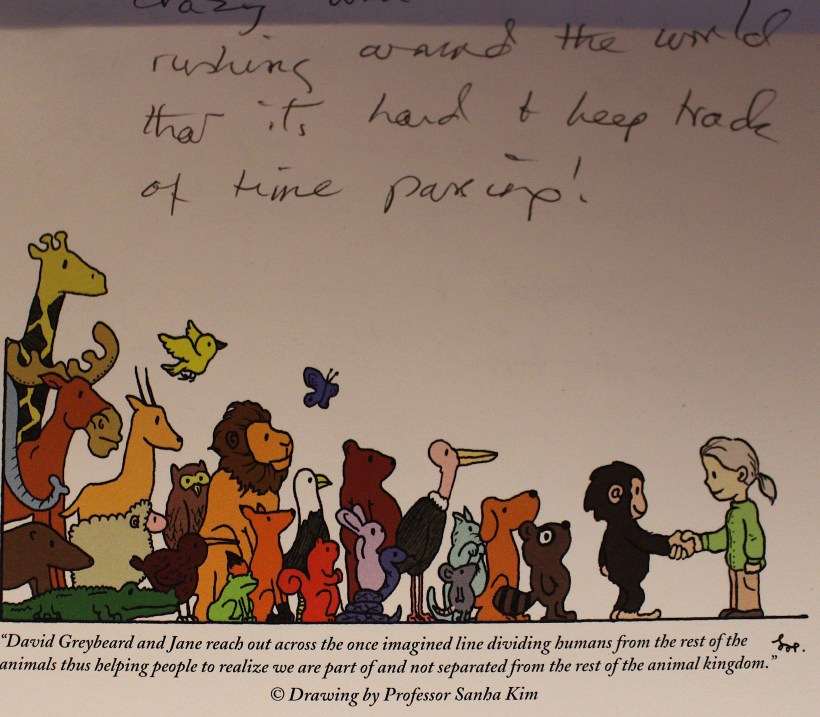

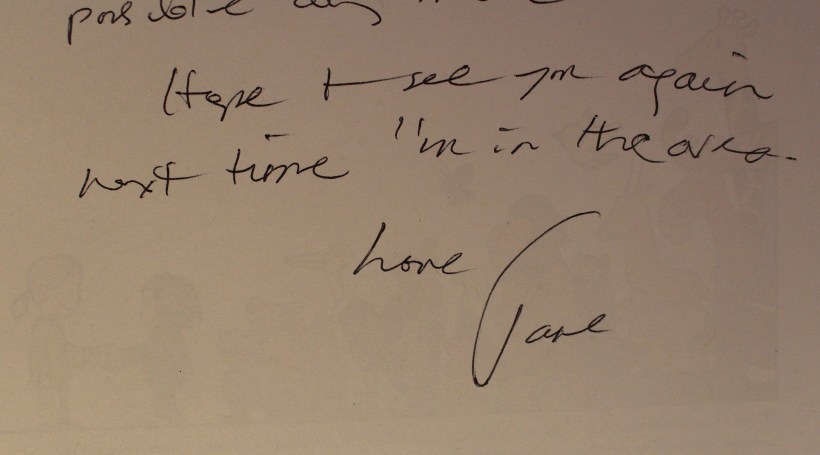

True to Jane’s tradition of impeccable graciousness, she sent me a hand-written note after her last visit in 2018 when she came to speak at Western Washington University in Bellingham.

I recommend the documentary “Jane” as the best review of Jane’s Gombe work. The Jane Goodall Institute will continue her legacy for decades to come.