Fall begins again even though I’m unprepared. No matter which way I turn, autumn’s kaleidoscope displays new patterns, new colors, new empty spaces as I watch the world die into itself once again.

Some dying blazes out in fury — a calling out for attention. Then there is the dying that happens without anyone taking much notice: a plain, tired, rusting away letting go.

I spent the morning adjusting to this change in season by occupying myself with the familiar task of moving manure. Cleaning barn is a comforting chore, allowing me to transform tangible benefit from something objectionable and just plain stinky to the nurturing fertilizer of the future. It feels like I’ve actually accomplished something.

As I scooped and pushed the wheelbarrow, I remembered another barn cleaning fifteen years ago, when I was one of a few friends left cleaning over ninety stalls after a Haflinger horse event that I had organized at our local fairgrounds. Some people had brought their horses from over 1000 miles away to participate for several days. There had been personality clashes and harsh words among some participants along with criticism directed at me that I had taken very personally. As I struggled with the umpteenth wheelbarrow load of manure, tears stung my eyes and my heart. I was miserable with regrets. After going without sleep and making personal sacrifices over many months planning and preparing for the benefit of our group, my work felt like it had not been acknowledged or appreciated.

A friend had stayed behind with her family to help clean up the large facility and she could see I was struggling to keep my composure. Jenny put herself right in front of my wheelbarrow and looked me in the eye, insisting I stop working for a moment and listen.

“You know, none of these troubles and conflicts will amount to a hill of beans years from now. People will remember a fun event in a beautiful part of the country, a wonderful time with their horses, their friends and family, and they’ll be all nostalgic about it, not giving a thought to the infighting or the sour attitudes or who said what to whom. We are horse people and human beings, for Pete’s sake, prone to complain and grouse about life. So don’t make this about you and whether you did or didn’t make everyone happy. You loved us all enough to make it possible to meet here and the rest was up to us. So quit being upset about what you can’t change. There’s too much you can still do for us.”

During tough times, Jenny’s advice replays, reminding me to stop expecting or seeking appreciation from others, or feeling hurt when harsh words come my way. She was right about the balm found in the tincture of time and she was right about giving up the upset in order to die to self and self absorption, and keep focusing outward.

I have remembered.

Subsequently, unknown to both of us at the time, Jenny herself spent over six years dying from breast cancer, while living her life sacrificially and sacramentally every day, fighting a relentless disease that was, for a time, immobilized in the face of her faith and intense drive to live. She became a rusting leaf, fading imperceptibly over time, crumbling at the edges until the day when she finally let go. Her dying did not flash brilliance, nor draw attention at the end. Her intense focus during the years of her illness had always been outward to others, to her young family and friends, to the healers she spent so much time with in medical offices, to her belief in the plan God had written for her and others.

So four years ago she let go her hold on life here. And we reluctantly have let her go. Brilliance now cloaks her as her focus is on things eternal.

You were so right, Jenny. Nothing from fifteen years ago amounts to a hill of beans; it simply doesn’t matter any more.

Except the words you spoke to me.

And I won’t be upset that I can’t change the fact that you have left us.

We’ll catch up later.

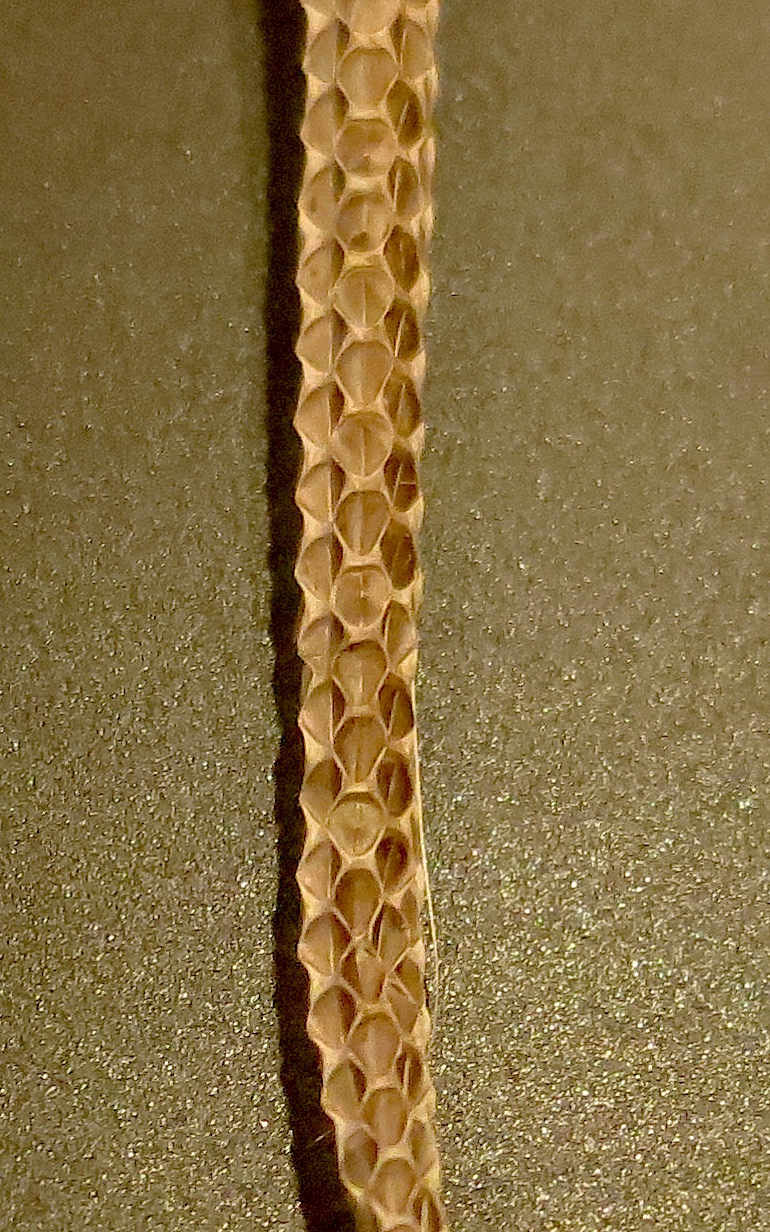

photo of Jenny Rausch in her last year on earth, by sister Ginger-Kathleen Coombs

photo of Jenny Rausch in her last year on earth, by sister Ginger-Kathleen Coombs