From my six week psychiatric inpatient rotation at a Veteran’s Hospital—February/March 1979

Sixty eight year old male catatonic with depression

He lies still, so very still under the sheet, eyes closed; the only clue that he is living is the slight rise and fall of his chest. His face is skull like with bony prominences framing his sunken eyes, his facial bones standing out like shelves above the hollows of his cheeks, his hands lie skeletal next to an emaciated body. He looks as if he is dying of cancer but without the smell of decay. He rouses a little when touched, not at all when spoken to. His eyes open only when it is demanded of him, and he focuses with difficulty. His tongue is thick and dry, his whispered words mostly indecipherable, heard best by bending down low to the bed, holding an ear almost to his cracked lips.

He has stopped feeding himself, not caring about hunger pangs, not salivating at enticing aromas or enjoying the taste of beloved coffee. His meals are fed through a beige rubber tube running through a hole in his abdominal wall emptying into his stomach, dripping a yeasty smelling concoction of thick white fluid full of calories. He ‘eats’ without tasting and without caring. His sedating antidepressant pills are crushed, pushed through the tube, oozing into him, deepening his sleep, but are designed to eventually wake him from his deep debilitating melancholy.

After two weeks of treatment and nutrition, his cheeks start to fill in, and his eyes are closed less often. He watches people as they move around the room and he responds a little faster to questions and starts to look us in the eye. He asks for coffee, then pudding and eventually he asks for steak. By the third week he is sitting up in a chair, reading the paper.

After a month, he walks out of the hospital, 15 pounds heavier than when he was wheeled in. His lips, no longer dried and cracking, have begun to smile again.

****************************************************************************************************************************

Thirty two year old male rescued by the Coast Guard at 3 AM in the middle of the bay

As he shouts, his eyes dart, his voice breaks, his head tosses back and forth, his back arches and then collapses as he lies tethered to the gurney with leather restraints. He writhes constantly, his arm and leg muscles flexing against the wrist and ankle bracelets.

“The angels are waiting!! They’re calling me to come!! Can’t you hear them? What’s wrong with you? I’m Jesus Christ, King of Kings!! Lord of Lords!! If you don’t let me return to them, I can’t stop the destruction!”

He finally falls asleep by mid-morning after being given enough antipsychotic medication to kill a horse. He sleeps uninterrupted for nine hours. Then suddenly his eyes fly open, and he looks startled.

He glares at me. “Where am I? How did I get here?”

“You are hospitalized in the VA psych ward after being picked up by the Coast Guard after swimming out into the bay in the middle of the night. You said you were trying to reach the angels.”

He turns his head away, his fists relaxing in the restraints, and begins to weep uncontrollably, the tears streaming down his face.

“Forgive them, Father, for they know not what they do.”

*********************************************************************************************************************************

Twenty two year old male with auditory and visual hallucinations

He seems serene, much more comfortable in his own skin when compared to the others on the ward. Walking up and down the long hallways alone, he is always in deep conversation. He takes turns talking, but more often is listening, nodding, almost conspiratorial.

During a one-on-one session, he looks at me briefly, but his attention continues to be diverted, first watching an invisible something or someone enter the room, move from the door to the middle of the room, until finally, his eyes lock on an empty chair to my left. I ask him what he sees next to me.

“Jesus wants you to know He loves you.”

It takes all my will power not to turn and look at the empty chair.

**************************************************************************************************************************************

Fifty four year old male with chronic paranoid schizophrenia

He has been disabled with psychiatric illness for thirty years, having his first psychotic break while serving in World War II. His only time living outside of institutions has been spent sharing a home with his mother who is now in her eighties. This hospitalization was precipitated by his increasing delusion that his mother is the devil and the voices in his head commanded that he kill her. He had become increasingly agitated and angry, had threatened her with a knife, so she called the police, pleading with them not to arrest him, but to bring him to the hospital for medication adjustment.

His eyes have taken on the glassy staring look of the overmedicated psychotic, and he sits in the day room much of the day sleeping in a chair, drool dripping off his lower lip. When awake he answers questions calmly and appropriately with no indication of the delusions or agitation that led to his hospitalization. His mother visits him almost daily, bringing him his favorite foods from home which he gratefully accepts and eats with enthusiasm. By the second week, he is able to take short passes to go home with her, spending a lunch time together and then returning to the ward for dinner and overnight. By the third week, he is ready for discharge, his mother gratefully thanking the doctors for the improvement she sees in her son. I watch them walk down the long hallway together to be let through the locked doors to freedom.

Two days later, a headline in the local paper:

“Veteran Beheads Elderly Mother”

*************************************************************************************************************************************

Forty five year old male — bipolar disorder with psychotic features

He has been on the ward for almost a year, his unique high pitched laughter heard easily from behind closed doors, his eyes intense in his effort to conceal his struggles. Trying to follow his line of thinking is challenging, as he talks quickly, with frequent brilliant off topic tangents, and at times he lapses into a “word salad” of almost nonsensical sentences. Every day as I meet with him I become more confused about what is going on with him, and am unclear what is expected of me in my interactions with him. He senses my discomfort and tries to ease my concern.

“Listen, this is not your problem to fix but I’m bipolar and regularly hear command voices and have intrusive thoughts. My medication keeps me under good control. But just tell me if you think I’m not making sense because I don’t always recognize it in myself.”

During my rotation, his tenuous tether to sanity is close to breaking. He starts to listen more intently to the voices in his head, becoming frightened and anxious, often mumbling and murmuring under his breath as he goes about his day.

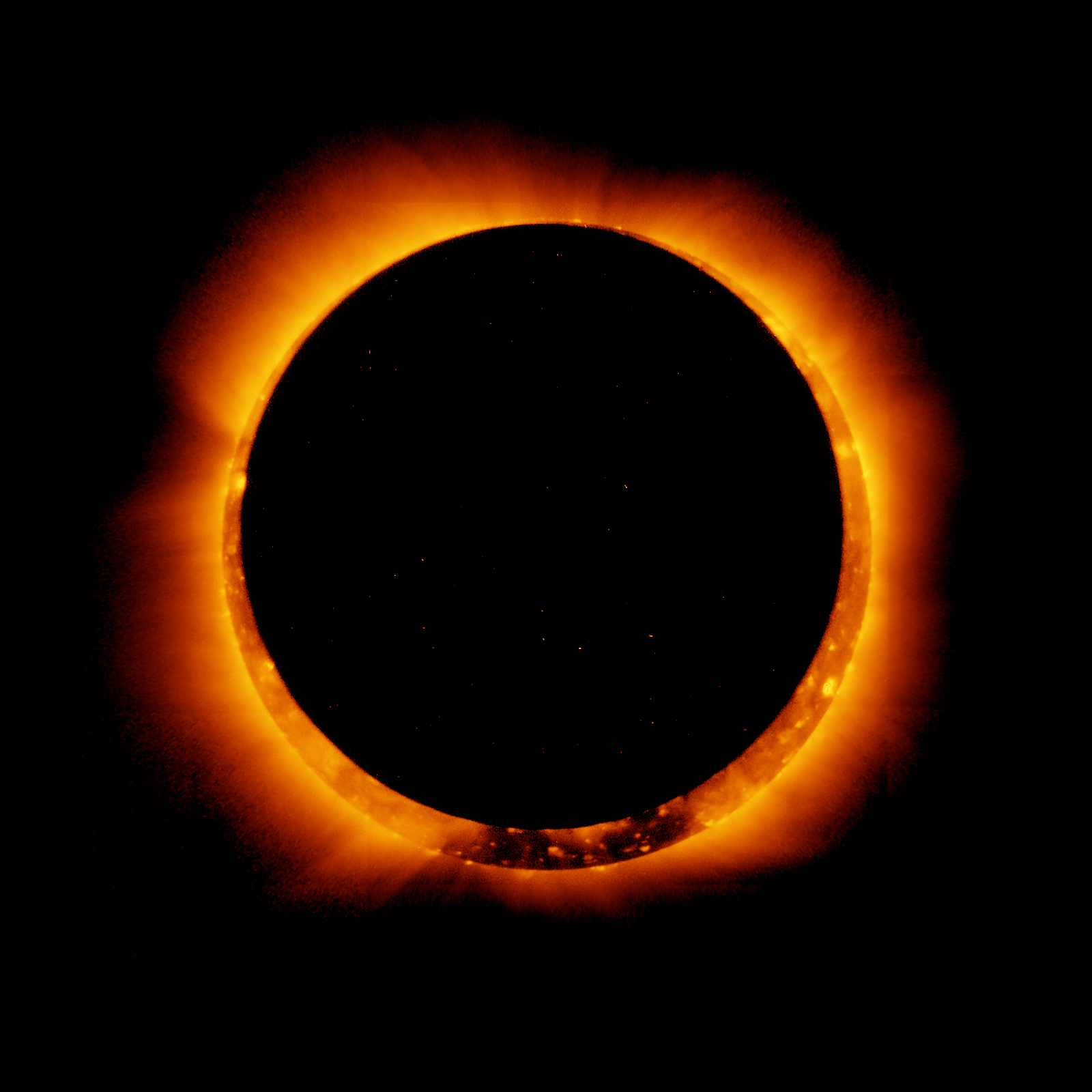

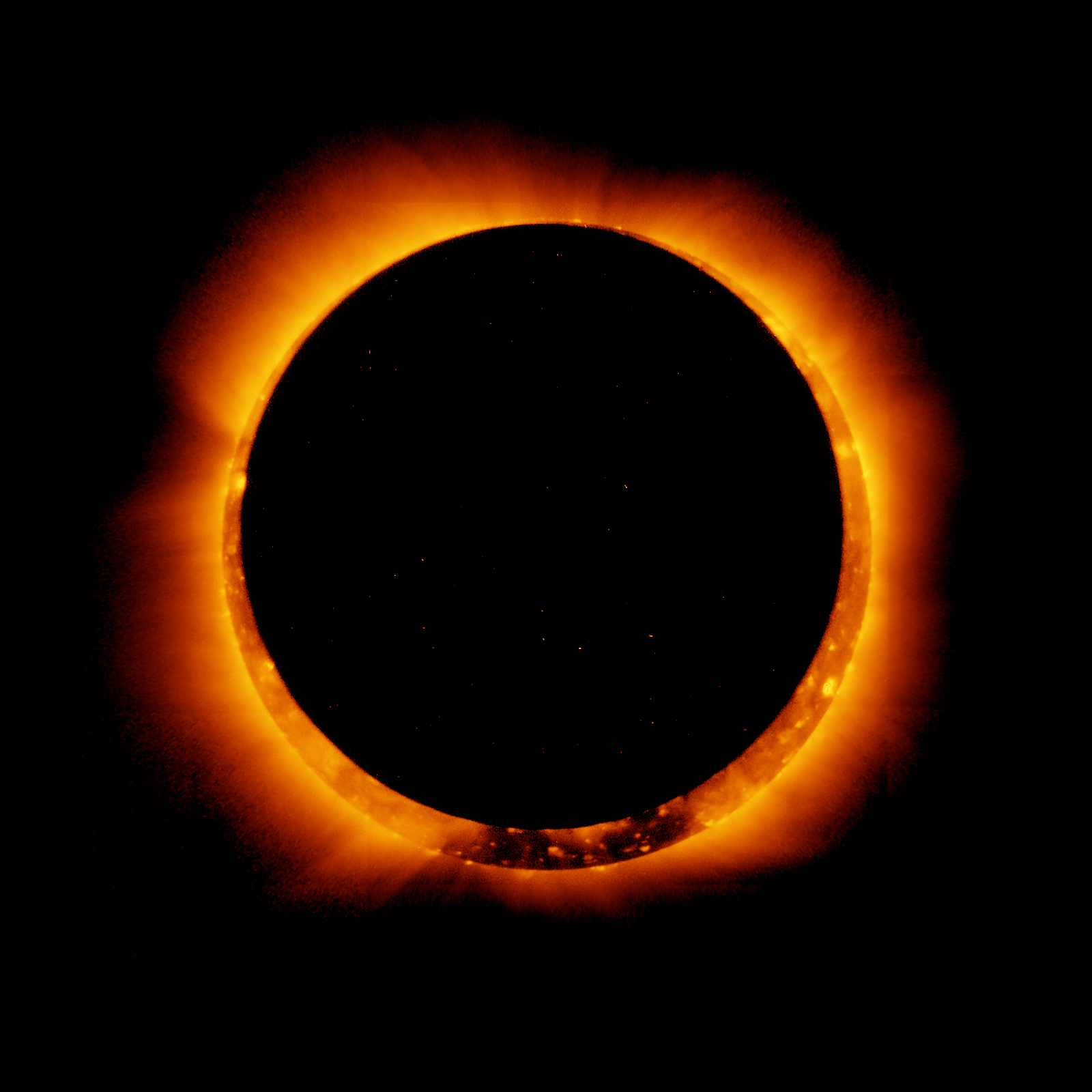

On this particular morning, all the patients are more anxious than usual, pacing and wringing their hands as the light outdoors slowly fades, with noon being transformed to an oddly shadowy dusk. The street lights turn on automatically and cars are driving with headlights shining. We stand at the windows in the hospital, watching the city become dark as night in the middle of the day. The unstable patients are sure the world is ending and extra doses of medication are dispensed as needed while the light slowly returns to the streets outside. Within an hour the sunlight is back, and all the patients are napping soundly.

The psychiatrist, now floridly psychotic, locks himself in his office and doesn’t respond to knocks on the door or calls on his desk phone.

Stressed by the recent homicide by one of his discharged patients, and identifying too closely with his patients due to his own mental illness, he is overwhelmed by the eclipse. The nurses call the hospital administrator who comes to the ward with two security guards. They unlock the door and lead the psychiatrist off the ward. We watch him leave, knowing he won’t be back.

It is as if the light left and only shadow remains.