There was never a sound beside the wood but one,

And that was my long scythe whispering to the ground.

What was it it whispered? I knew not well myself;

Perhaps it was something about the heat of the sun,

Something, perhaps, about the lack of sound—

And that was why it whispered and did not speak.

To the earnest love that laid the swale in rows,

The fact is the sweetest dream that labor knows.

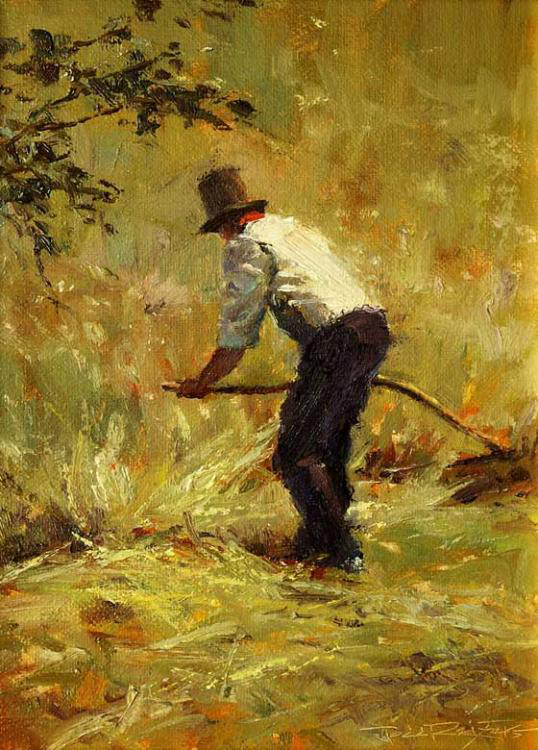

My long scythe whispered and left the hay to make.

~Robert Frost in “Mowing”

Mowers, weary and brown, and blithe,

What is the word methinks ye know,

Endless over-word that the Scythe

Sings to the blades of the grass below?

Scythes that swing in the grass and clover,

Something still, they say as they pass;

What is the word that, over and over,

Sings the Scythe to the flowers and grass?

Hush, ah hush, the Scythes are saying,

Hush, and heed not, and fall asleep;

Hush, they say to the grasses swaying,

Hush, they sing to the clover deep!

Hush – ’tis the lullaby Time is singing –

Hush, and heed not, for all things pass,

Hush, ah hush! and the Scythes are swinging

Over the clover and over the grass!

~Andrew Lang (1844-1912) “The Scythe Song”

It is blue May. There is work

to be done. The spring’s eye blind

with algae, the stopped water

silent. The garden fills

with nettle and briar.

Dylan drags branches away.

I wade forward with my scythe.

There is stickiness on the blade.

Yolk on my hands. Albumen and blood.

Fragments of shell are baby-bones,

the scythe a scalpel, bloodied and guilty

with crushed feathers, mosses, the cut cords

of the grass. We shout at each other

each hurting with a separate pain.

From the crown of the hawthorn tree

to the ground the willow warbler

drops. All day in silence she repeats

her question. I too return

to the place holding the pieces,

at first still hot from the knife,

recall how warm birth fluids are.

~Gillian Clarke “Scything” from Letter from a Far Country (1982)

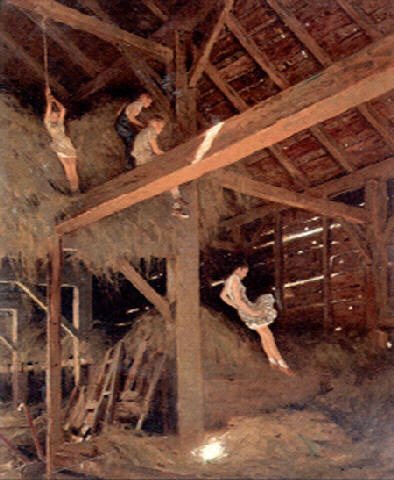

The grass around our orchard and yet-to-be-planted garden is now thigh-high. It practically squeaks while it grows. Anything that used to be in plain sight on the ground is rapidly being swallowed up in a sea of green: a ball, a pet dish, a garden gnome, a hose, a tractor implement, a bucket. In an effort to stem this tidal flood of grass, I grab the scythe out of the garden shed and plan my attack.

When the pastures are too wet yet for heavy hooves, I have hungry horses to provide for and there is more than plenty fodder to cut down for them.

I’m not a weed whacker kind of gal. First there is the necessary fuel, the noise necessitating ear plugs, the risk of flying particles requiring goggles–it all seems too much like an act of war to be remotely enjoyable. Instead, I have tried to take scything lessons from my husband.

Emphasis on “tried.”

I grew up watching my father scythe our hay in our field because he couldn’t afford a mower for his tractor. He enjoyed physical labor in the fields and woods–his other favorite hand tool was a brush cutter that he’d take to blackberry bushes. He would head out to the field with the scythe over this shoulder, grim reaper style. Once he was standing on the edge of the grass needing to be mowed, he would then lower the scythe, curved blade to the ground, turn slightly, positioning his hands on the two handles just so, raise the scythe up past his shoulders, and then in a full body twist almost like a golf swing, he’d bring the blade down. It would follow a smooth arc through the base of the standing grass, laying clumps flat in a tidy pile alongside the 2 inch stubble left behind. It was a swift, silky muscle movement — a thing of beauty.

Once, when I was three years old, I quietly approached my dad in the field while he was busily scything grass for our cows, but I didn’t announce my presence. The handle of his scythe connected with me as he swung it, laying me flat with a bleeding eyebrow. I still bear the scar, somewhat proudly, as he abruptly stopped his fieldwork to lift me up as I bawled and bled on his sweaty shirt. He must have felt so badly to have injured his little girl and drove my mom and I to the local doctor who patched my brow with sticky tape rather than stitches.

So I identify a bit with the grass laid low by the scythe. I forgave my father, of course, and learned never again to surprise him when he was working in the field.

Instead of copying my father’s graceful mowing technique, I tended to chop and mangle rather than effect an efficient slicing blow to the stems. I unintentionally trampled the grass I meant to cut. I got blisters from holding the handles too tightly. It felt hopeless that I’d ever perfect that whispery rise and fall of the scythe, with the rhythmic shush sound of the slice that is almost hypnotic.

Not only did I become an ineffective scything human, I also learned what it is like to be the grass laid flat, on the receiving end of a glancing blow. Over a long career, I bore plenty of footprints from the trampling. It can take awhile to stand back up after being cut down.

Sometimes it makes more sense to simply start over as the oozing stubble bleeds green, with deep roots that no one can reach. As I have grown back over the years, singing rather than squeaking or bawling, I realize, I forgave the scythe every time it came down on my head.

Make a one-time or recurring donation to support daily Barnstorming posts

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is deeply appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly