Seventy years ago my maternal grandmother, having experienced months of fatigue, abdominal discomfort and weight loss, underwent exploratory abdominal surgery, the only truly diagnostic tool available at the time. One brief look by the surgeon told him everything he needed to know: her liver and omentum were riddled with tumor, clearly advanced, with the primary source unknown and ultimately unimportant. He quickly closed her up and went to speak with her family–my grandfather, uncle and mother. He told them there was no hope and no treatment, to take her back home to their rural wheat farm in the Palouse country of Eastern Washington and allow her to resume what activities she could with the time she had left. He said she had only a few months to live, and he recommended that they simply tell her that no cause was found for her symptoms.

So that is exactly what they did. It was standard practice at the time that an unfortunate diagnosis be kept secret from terminally ill patients, assuming the patient, if told, would simply despair and lose hope. My grandmother was gone within a few weeks, growing weaker and weaker to the point of needing rehospitalization prior to her death. She never was told what was wrong and, more astonishing, she never asked.

But surely she knew deep in her heart. She must have experienced some overwhelmingly dark moments of pain and anxiety, never hearing the truth so that she could talk about it with her physician and those she loved. But the conceit of the medical profession at the time, and indeed, for the next 20-30 years, was that the patient did not need to know, and indeed could be harmed by information about their illness. We modern more enlightened health care professionals know better. We know that our physician predecessors were avoiding uncomfortable conversations by exercising the “the patient doesn’t need to know and the doctor knows better” mandate. The physician had complete control of the health care information–the details of the physical exam, the labs, the xray results, the surgical biopsy results–and the patient and family’s duty was to follow the physician’s dictates and instructions, with no questions asked.

Even during my medical training in the seventies, there was still a whiff of conceit about “the patient doesn’t need to know the details.” During rounds, the attending physician would discuss diseases right across the hospital bed over the head of the afflicted patient, who would often worriedly glance back and worth at the impassive faces of the intently listening medical student, intern and resident team. There would be the attending’s brief pat on the patient’s shoulder at the end of the discussion when he would say, “someone will be back to explain all this to you.” But of course, none of us really wanted to and rarely did.

Eventually I did learn how important it was to the patient that we provide that information. I remember one patient who spoke little English, a Chinese mother of three in her thirties, who grabbed my hand as I turned to leave with my team, and looked me in the eye with a desperation I have never forgotten. She knew enough English to understand that what the attending had just said was that there was no treatment to cure her and she only had weeks to live. Her previously undiagnosed pancreatic cancer had caused a painless jaundice resulting in her hospitalization and the surgeon had determined she was not a candidate for a Whipple procedure. When I returned to sit with her and her husband to talk about her prognosis, I laid it all out for them as clearly as I could. She thanked me, gripping my hands with her tear soaked fingers. She was so grateful to know what she was dealing with so she could make her plans, in her own way.

Thirty years into my practice of medicine, I now spend a significant part of my patient care time in providing information that helps the patient make plans, in their own way. I figure everything I know needs to be shared with the patient, in real time as much as possible, with all the options and possibilities spelled out. That means extra work, to be sure, and I spend extra time on patient care after hours more than ever before in my efforts to communicate with my patients. Every electronic medical record chart note I write is sent online to the patient via a secure password protected web portal, usually from the exam room as I talk with the patient. Patient education materials are attached to the progress note so the patient has very specific descriptions, instructions and further web links to learn more about the diagnosis and my recommended treatment plan. If the diagnosis is uncertain, then the differential is shared with the patient electronically so they know what I am thinking. The patient’s Major Problem List is on every progress note, as are their medications, dosages and allergies, what health maintenance measures are coming due or overdue, in addition to their “risk list” of alcohol overuse, recreational drug use, poor eating habits and tobacco history. Everything is there, warts and all, and nothing is held back from their scrutiny.

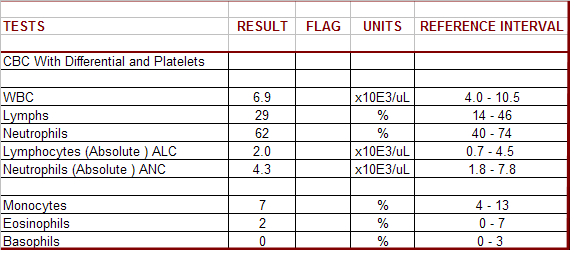

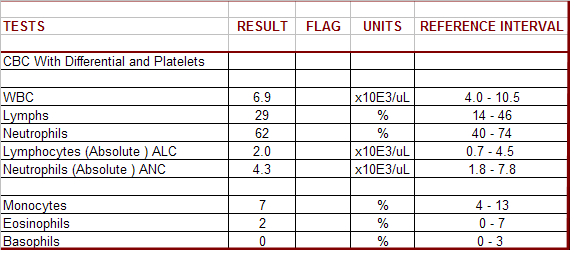

Within a few hours of their clinic visit, they receive their actual lab work and copies of imaging studies electronically, accompanied by an interpretation and my recommendations. No more “you’ll hear from us only if it is abnormal” or “it may be next week until you hear anything”. We all know how quickly most lab and imaging results, as well as pathology results are available to us as providers, and our patients deserve the courtesy of knowing as soon as we do, and now regulations insist that we share the results. Waiting for results is one of the most agonizing times a patient can experience. If it is something serious that necessitates a direct conversation, I call the patient just as I’ve always done. When I send electronic information to my patients, I solicit their questions, worries and concerns by return message. All of this electronic interchange between myself and my patient is recorded directly into the patient chart automatically, without the duplicative effort of having to summarize from phone calls.

In this new kind of health care team, the patient has become a true partner in their illness management and health maintenance because they now have the information to deal with the diagnosis and treatment plan. I don’t ever hear “oh, don’t bother me with the details, just tell me what you’re going to do.” I have never felt more empowered as a healer when I now can share everything I have available, as it becomes available. My patients are empowered in their pursuit of well-being, whether living with chronic illness, or recovering from acute illness. No more secrets. No more power differential. No more “I know best.”

After all, it is my patient’s life I am impacting by providing them unrestricted access to the self-knowledge that leads them to a better appreciation for their health and and understanding of their illnesses.

And so I am impacted as well, as it is a privilege to live and work in an age where such a doctor~patient relationship has now become possible.