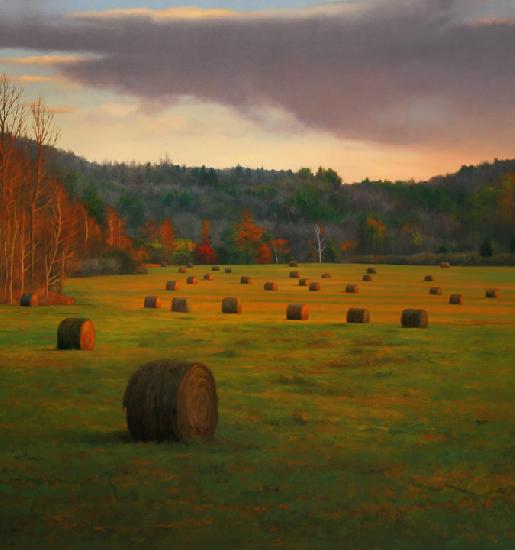

Let the light of late afternoon

shine through chinks in the barn, moving

up the bales as the sun moves down.

Let it come, as it will, and don’t

be afraid. God does not leave us

comfortless, so let evening come.

from “Let Evening Come” by Jane Kenyon

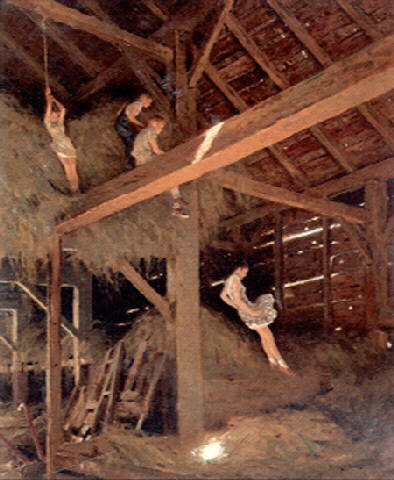

During our northwest winters, there is so little sunlight on gray cloudy days that I routinely turn on the two light bulbs in the big hay barn any time I need to go in to fetch hay bales for the horses. This is to help me avoid falling into the holes that inevitably develop in the hay stack between bales. The murky lighting tends to hide the dark shadows of the leg-swallowing pits among the bales, something that is particularly hazardous when carrying a 60 pound hay bale.

When I went to feed the horses at sunset tonight, I looked up at the lights blazing in the hay barn and went to the light switch to shut them off, but the switch was already off. Puzzled, I realized that lighting up the barn was a precise angle of the setting sun, not light bulbs at all. The last of the day’s sun rays were streaming through the barn slat openings, richocheting off the roof timbers onto the bales, casting an almost fiery glow onto the hay. The barn was ignited and ablaze without fire and smoke which are the last things one would even want in a hay barn. I could scramble among the bales without worry to get my chores accomplished.

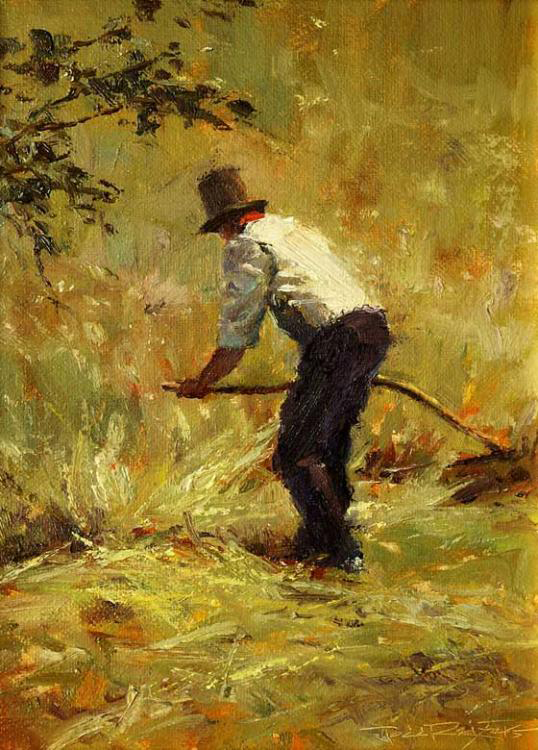

It seems even in my life outside the barn I’ve been falling into more than my share of dark holes lately. Even when I know where they lie and how deep they are, some days I will manage to step right in anyway. Each time it knocks the breath out of me, makes me cry out, makes me want to quit trying to lift the heavy loads. It leaves me fearful to even venture out.

Then, amazingly, a light comes from the most unexpected of places, blazing a trail to help me see where to step, what to avoid, how to navigate the hazards to avoid collapsing on my face. I’m redirected, inspired anew, granted grace, gratefully calmed and comforted amid my fears. Even though the light fades, and the darkness descends again, it is only until tomorrow. Then it will reignite again.

The light returns and so will I.