This story, written in 2003, is now published in the Oct/Nov 2009 issue of Country Magazine. Photos by Lynden Christian student Krisula Steiger.

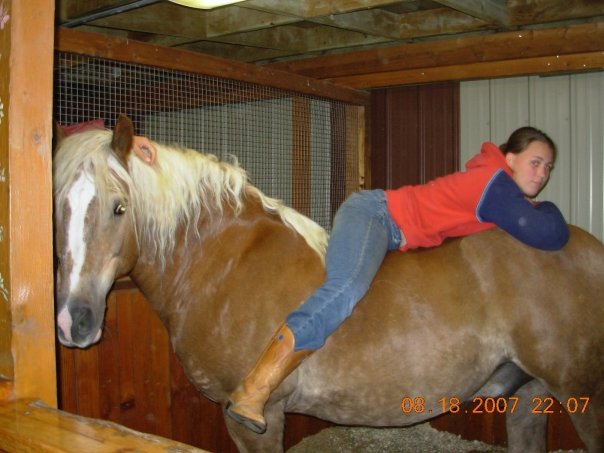

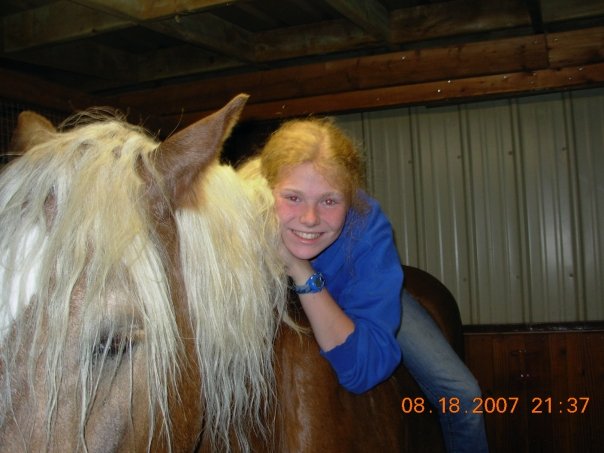

Generally late September is when we start to see our Haflinger horses growing in their longer coat for winter. Their color starts to deepen with the new hair as the sun bleached summer coat loosens and flies with the late summer breezes. The nights here, when the skies are cloudless, can get perilously close to freezing this time of year, though our first frost is generally not until well into October. The Haflingers, outside during the day, and inside their snug stalls at night, don’t worry too much about needing their extra hair quite yet, especially when the day time temperatures are still comfortably in the 70s. So they are not in a hurry to be furrier. Neither am I. But I enjoy watching this daily change in their coats, as if they were ripening at harvest time. Their copper colors are so rich against the green fields and trees, especially at sunset when the orange hue of their coat is enhanced by the sunlit color palette of fall leaves undergoing their own transformation in their dying.

In another six months, it will be a reverse process once again. This heavy hair will have served its purpose, dulled by the harsh weather it has been exposed to, and coming out in clumps and tufts, revealing that iridescent short hair summer coat that shines and shimmers metallic in comparison, although several shades lighter, sometimes with nuances of dapples peeking through. Metamorphosis from fur ball to copper penny.

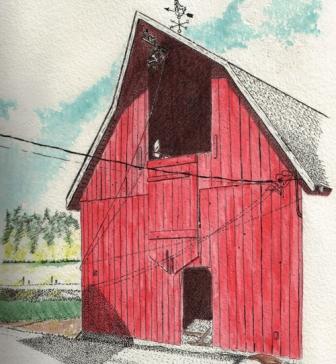

It occurs to me our old barn buildings on our farm have also undergone a similar transformation, having received a new coat of paint this summer. As a dairy farm for its previous owners starting in the early 1900s until a few years before we purchased it in the late 80s, it has accumulated more than its share of sheds and buildings constructed over the years to serve one purpose or another: the big hay barn with mighty old growth beams and timbers in its framework (still hay storage), the attached milking parlor (converted by us to individual box stalls for our weanlings and yearlings) and milk house where the bulk tank once stood, the older separate milk house where the milk used to be stored in cans waiting for pick up by the milk truck (now garden shed and harness storage), the old smoke house for smoking meats (was our chicken coop, but now the dogs claim it), the old bunk house and root cellar (more storage), the old large chicken coop (now parking for our carts and carriage), and the garage (a Methodist church in its former life and moved 1/4 mile up the road to our farm some 70 years ago when the little community of Forest Grove that had formed around a saw mill, store, school and church disbanded after 30 years of prosperity when there were no more trees to cut down in the area). When we bought this farm, these buildings had not seen a coat of paint in many many years. They were weathering badly–we set to work right away in an effort to save them if we could, and got them repainted–“barn red” for the barn and cream white for the other buildings with red trim around the windows and roof lines.

That was over 10 years ago now and we’ve been trying to hold off on another round of painting but it was clear this summer that it needed to happen. Now that they have their fresh paint coats, these old buildings appear to have new life again, though it is only on the surface. We know there are roofs that need patching, wiring that needs to be redone, plumbing that needs repair, foundations that need shoring up, windows that are drafty and need replacing, doors that don’t shut properly anymore–the list goes on. That superficial coat of paint does not solve all those problems–it will help prolong the life of the buildings, to be sure, but in many ways, all we’ve done is cosmetic surgery. What we really need is a full time carpenter –which neither of us is and at this point can’t afford.

In my middle age, there are times when I wish fervently for that “new coat” for myself–i.e. fewer gray hairs, fewer pounds, fewer wrinkles and one less chin, less achy stronger muscles. I buy a new fall jacket and realize that all my deficiencies are simply covered for the time being. I may be warmer but I’m not one bit younger. That jacket will, I hope, protect me from the brisk northeast winds and the incessant drizzle of the region, but it will not stop the inevitable underneath. It will not change who I am and what I will become.

True change can only come from within, from deep inside our very foundations, requiring a transforming influence that comes from outside. For the Haflingers, it is the diminishing light and lower temperatures. For the buildings, it is the hammer and nail, and the capable hands that wield them. For me, it is knowing there is salvage for people too, not just for old barns and sheds. Our foundations are hoisted up and reinforced, and we’re cleaned, patched and saved despite who we have become. And unlike new paint, or a winter coat, it lasts forever.

(published a year ago in Country Magazine)

(published a year ago in Country Magazine)

We’ve often been asked about the origin of our farm name, BriarCroft, as it is a bit unusual. I point toward our back field when I explain: banks of blackberry bushes and vines on the periphery of our woods, covering an old barbwire fence, and literally becoming fence itself in their overwhelming growth. So that is the “briar” and the “croft” is our little Scottish “farm on a hill”.

We’ve often been asked about the origin of our farm name, BriarCroft, as it is a bit unusual. I point toward our back field when I explain: banks of blackberry bushes and vines on the periphery of our woods, covering an old barbwire fence, and literally becoming fence itself in their overwhelming growth. So that is the “briar” and the “croft” is our little Scottish “farm on a hill”.