All of us come to the study and practice of medicine through different pathways: some because of family members who were doctors or patients, some out of our own illness or woundedness, some out of intense drive to achieve and serve.

I came to medicine because of my grade school classmate Michael.

My grade school represented a grand social experiment of the early 1960’s. It was one of the first schools to mainstream special needs children into “regular” classrooms. At that time, the usual approach was to warehouse kids with disabilities (i.e. “handicaps” in 60′s parlance) in separate rooms, if not whole separate schools.

During those years, the average class size for a grade school teacher was 32-35 kids, with no teacher’s aides, rare parent volunteers (except for field trips and room mothers who threw the holiday parties) and no medications or special accommodations for ADHD or learning disabilities. I’m not sure how teachers coped with a room full of too-often noisy unruly kids, but somehow they managed to teach in spite of the obstacles. Adding in children with mental and physical challenges without additional adult help must have been very difficult.

So the more capable kids got recruited to mentor the kids with disabilities. It was a way to keep some kids busy who out of boredom might otherwise find themselves engaging in disruptive entertainment. It helped the teacher by creating a buddy system for the special needs kids who might need help with class work or who might have difficulty getting around.

I was assigned to Michael. He was a spindly boy with cerebral palsy and hearing aids, thick glasses hooked with a wide band around the back of his head, and spastic muscles that never seemed to go where he wanted them to go. He walked independently with some difficulty, mostly on his tiptoes because of his shortened leg muscles, falling when he got going too quickly as his thick orthopedic shoes with braces would trip him up. His hands were intermittently in a crab like grip of contracted muscles, and his face always contorting and grimacing. He drooled continuously so perpetually carried a Kleenex in his hand to catch the drips of spit that ran out of his mouth and dropped on his desk, threatening to spoil his coloring and writing papers.

His speech consisted of all vowels, as his tongue couldn’t quite connect with his teeth or palate to sound out the consonants, so it took some time and patience to understand what he said. He could write with great effort, gripping the pencil awkwardly in his tight palm and found he could communicate better at times on paper than by talking. I made sure he had help to finish assignments if his muscles were too tight to write, and I learned his language so I could interpret for the teacher. He was brave and bright, with a finer mind than most of the kids in our class. He loved a good joke and his little body would shudder as he roared his appreciation. I was always impressed at how he expressed himself and how little bitterness he had about his limitations.

He was the most articulate inarticulate person I knew. As an eleven year old peer-opinion-driven preadolescent girl, I’m amazed I could even recognize that about Michael. It was so tempting to be oblivious and insensitive to the person that Michael was inside his disabled shell.

Sometimes I wanted to hide as Michael appeared around the corner of the grade school building every morning. He would be walking too quickly in his careful tip-toe cadence, arms flailing, shoes scuffing, raising up dust with each step. He would wave at me and call out my name in his indecipherable voice, a voice I knew all too well.

There were many times when I resented being Michael’s buddy, socially crippled myself in my 5th grade need to be popular and acceptable to my peers. I didn’t want to be constantly responsible for him and my friends teased me about him being my boyfriend. And in many ways, he was just that.

As he would approach while I stood in my clump of friends on the playground, a group of boys playing tag would swoop past him, purposely a little too close, spinning him off his feet like a top and onto the ground. Glasses askew, he would lay momentarily still, and realizing I was needed, I would run to his side. Despite all he endured, I never saw Michael cry, not even once, not even when he fell down hard. When he got angry or frustrated, he’d get very quiet, but his muscles would tense up so much he would go into even greater spasms.

I would help him up, brush off the playground dirt from his sweatshirt and pants and look at his grimacing face. Although he would give me a huge toothy smile of thanks, his eyes, as usual, said what his mouth could not. He looked right past my hardened preadolescent pretense, into my softening heart. Michael knew I needed him as much as he needed me. I was a lifesaver that had been thrown to him as he struggled to stay afloat in the sea of playground hostility. And he was the first boy who loved me because of who he saw beneath my outer shell.

After two years, the social experiment was over and the school segregated the special needs kids back to therapeutic educational classrooms. Though I never saw Michael again, I heard him on the radio six years later, reading an essay he’d written for the local Voice of Democracy contest on what it meant to be a free citizen. His speech was one of the top three award winners that year. I was so proud of how he’d done and how understandable his speaking voice had become.

I’ve thought of him frequently over the years as I went on to medical school, knowing that my initial training in compassionate caring came as I sat by his side for hours, even when I didn’t want to be there, learning to understand his voice and his heart. I didn’t appreciate it then as I do now, but he taught me far more than I ever taught him: patience, perseverance and respect for the journey rather than the destination. He taught me life isn’t always fair so you make the best of what you are given.

Michael, wherever you are, you did that for me and it set me on the road to practice medicine. You helped me reach deep into my too often selfish heart to reach out to help others.

And in my own imperfect special needs way, I know I loved you too.

“That old September feeling, left over from school days, of summer passing… obligations gathering, books and football in the air … Another fall, another turned page: there was something of jubilee in that annual autumnal beginning, as if last year’s mistakes had been wiped clean by summer.”

“That old September feeling, left over from school days, of summer passing… obligations gathering, books and football in the air … Another fall, another turned page: there was something of jubilee in that annual autumnal beginning, as if last year’s mistakes had been wiped clean by summer.”

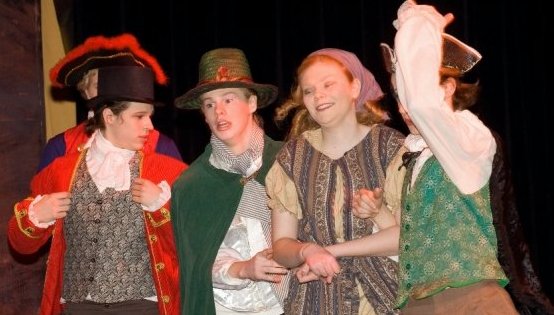

photos courtesy of Josh and Tim Scholten

photos courtesy of Josh and Tim Scholten