Big Foot, a great Chief of the Sioux often said,

“I will stand in peace till my last day comes.”

He did many good and brave deeds

for the white man and the red man.

Many innocent women and children who knew no wrong died here.

~Inscription on the Wounded Knee Monument

I did not know then how much was ended. When I look back now from this high hill of my old age, I can still see the butchered women and children lying heaped and scattered all along the crooked gulch as plain as when I saw them with eyes still young. And I can see that something else died there in the bloody mud, and was buried in the blizzard. A people’s dream died there. It was a beautiful dream. And I, to whom so great a vision was given in my youth, — you see me now a pitiful old man who has done nothing, for the nation’s hoop is broken and scattered. There is no center any longer, and the sacred tree is dead.

~Black Elk, (wounded trying to rescue his people after the Wounded Knee Massacre) from Black Elk Speaks

From today’s The Writer’s Almanac:

December 29 is the anniversary of the massacre at Wounded Knee, which took place in South Dakota in 1890. Twenty-three years earlier the local tribes had signed a treaty with the United States government that guaranteed them the rights to the land around the Black Hills, which was sacred land. The treaty said that not only could no one move there, but they couldn’t even travel through without the consent of the Indians.

But in the 1870s gold was discovered in the Black Hills and the treaty was broken. People from the Sioux tribe were forced onto a reservation with a promise of more food and supplies, which never came. Then in 1889 a native prophet named Wovoka, from the Paiute tribe in Nevada, had a vision of a ceremony that would renew the earth, return the buffalo, and cause the white men to leave and return the land that belonged to the Indians. This ceremony was called the Ghost Dance. People traveled across the plains to hear Wovoka speak, including emissaries from the Sioux tribe, and they brought back his teachings. The Ghost Dance, performed in special brightly colored shirts, spread through the villages on the Sioux reservation and it scared the white Indian agents. They considered the ceremony a battle cry, dangerous and antagonistic. So one of them wired Washington to say that he was afraid and wanted to arrest the leaders and he was given permission to arrest Chief Sitting Bull, who was killed in the attempt. The next on the wanted list was Sitting Bull’s half-brother, Chief Big Foot, known to his own people as Spotted Elk. Some members of Sitting Bull’s tribe made their way to Big Foot and when he found out what had happened he decided to lead them along with the rest of his people to Pine Ridge Reservation for protection. But it was winter, 40 degrees below zero, and he contracted pneumonia on the way.

Big Foot was sick, he was flying a white flag, and he was a peaceful man. He was one of the leaders who had actually renounced the Ghost Dance. But the Army didn’t make distinctions. They intercepted Big Foot’s band and ordered them into the camp on the banks of the Wounded Knee Creek. Big Foot went peacefully.

The next morning federal soldiers began confiscating their weapons and a scuffle broke out between a soldier and an Indian. The federal soldiers opened fire, killing almost 300 men, women, and children, including Big Foot. Even though it wasn’t really a battle, the massacre at Wounded Knee is considered the end of the Indian Wars, a blanket term to refer to the fighting between the Native Americans and the federal government, which had lasted 350 years.

One of the people wounded but not killed during the massacre was the famous medicine man Black Elk, author of Black Elk Speaks (1932). Speaking about Wounded Knee, he said:

“I did not know then how much was ended. When I look back now from this high hill of my old age, I can still see the butchered women and children lying heaped and scattered all along the crooked gulch as plain as when I saw them with eyes still young. And I can see that something else died there in the bloody mud, and was buried in the blizzard. A people’s dream died there. It was a beautiful dream.”

Like most twentieth century American children, I grew up with a sanitized understanding of American and Native history. I had only a superficial knowledge of what happened at Wounded Knee, a low hill that rises above a creek bed on the South Dakota Pine Ridge Reservation, gleaned primarily from the 71 day symbolic standoff in 1973 between members of the Oglala Sioux and the American Indian Movement and the FBI, resulting in several shooting deaths.

Nine years ago, when our son was teaching math at Little Wound High School on the Pine Ridge Reservation, we visited the site of this last major battle between the white man and Native people, which broke the spirit of the tribes’ striving to maintain their nomadic life as free people. This brutal massacre of nearly 300 Lakota men, women and children by the Seventh Regiment of the U.S. Army Cavalry took place in December 1890.

The dead lay where they fell for four days due to a severe blizzard. When the frozen corpses were finally gathered up by the Army, a deep mass grave was dug at the top of the hill, the bodies buried stacked one on top of another. The massive grave is now marked by a humble memorial monument surrounded by a chain link fence, adjacent to a small church, circled by more recent Lakota gravesites.

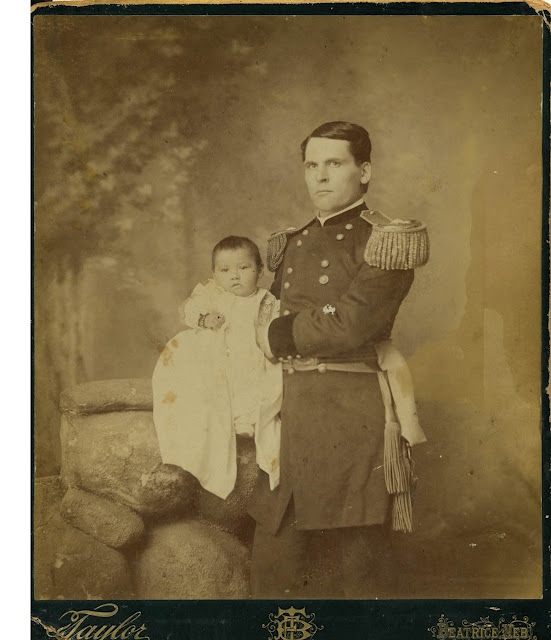

Four infants survived the four days of blizzard conditions wrapped in their dead mothers’ robes. One baby girl, only a few months old, was named “Lost Bird” after the massacre, bartered for and adopted by an Army Colonel as an interesting Indian “relic.” Rather than this adoption giving her a new chance, she died at age 29, having endured much illness, prejudice in white society, as well as estrangement from her native community and culture. Her story has been told in a book by Renee Sansom Flood, who helped to locate and move her remains back to Wounded Knee, where in death she is now back with her people.

There is unspeakable desolation and sadness on that lonely hill of graves. It is a regrettable part of our history that descendants of immigrants to American soil need to understand: by coming to the “New World” for opportunity, or refuge from oppression elsewhere, we made refugees of the people already here.

As Black Elk wrote, the dreams of a great people have been scattered and lack a center. He was not only speaking of his own tribe, but was presciently speaking of our current divisiveness – due to extremism, we lack “a center” in our current governmental discourse.

We must never allow hope to be buried at Wounded Knee nor must we ever forget what it means to no longer be safe in one’s own homeland.

Make a one-time or recurring donation to Barnstorming

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is deeply appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly