written September 11, 2001

written September 11, 2001

There are moments of epiphany in horse and family raising, and tonight brought one of those moments. The world suddenly feels so incredibly uncertain, yet simple moments of grace-filled routine offer themselves up unexpectedly, and I know the Lord is beside us no matter what has happened.

Tonight it was tucking the horses into bed, almost as precious to me as tucking our children into bed. In fact, my family knows I cannot sit down to dinner until the job is done out in the barn–so human dinner waits until horsie dinner is served and their beds prepared.

My work schedule is usually such that I must take the horses out to their paddocks from their cozy box stalls while the sky is still dark, and then bring them back in later in the day after the sun goes down. We have quite a long driveway from barn to the paddocks which are strategically placed by the road so the horses are exposed to all manner of road noise, vehicles, logging, milk and hay trucks, school buses, and never blink when these zip past their noses. They must learn from weanling stage on to walk politely and respectfully alongside me as I make that trek from the barn in the morning and back to the barn in the evening.

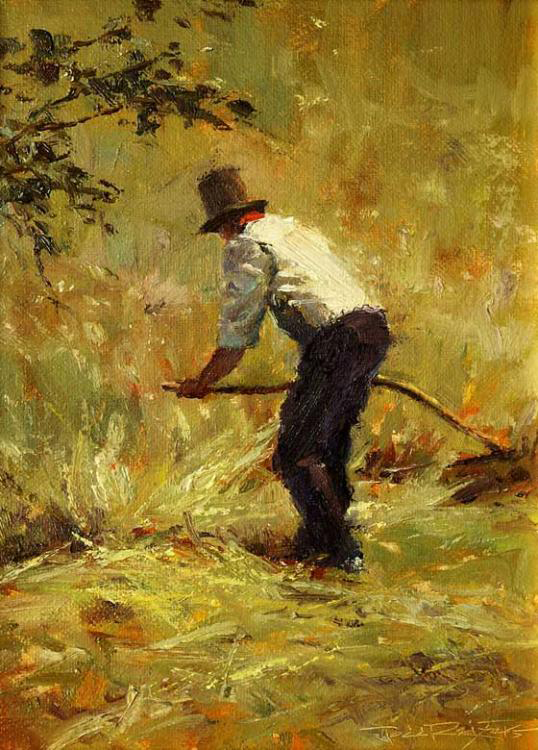

Bringing the horses in tonight was a particular joy because I was a little earlier than usual and not needing to rush: the sun was setting quite golden orange, the world had a glow, the poplar and maple leaves have carpeted the driveway and each horse walked with me without challenge, no rushing, pushing, or pulling–just walking alongside me like the partner they have been taught to be.

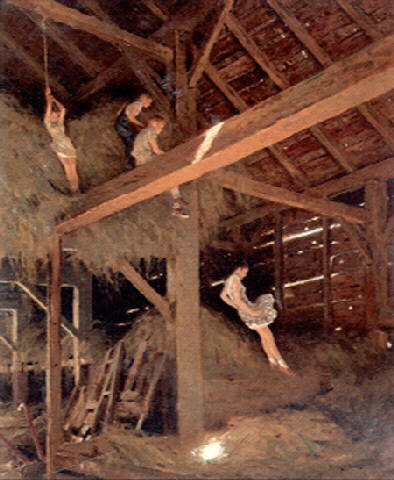

I enjoy putting each into their own box stall bed at night, with fresh fluffed shavings, a pile of sweet smelling hay and fresh water. I can feel them breathe this big sigh of relief that they have their own space for the night–no jostling for position or feed, no hierarchy for 12 hours, and then it is back out the next morning to the herd, with all the conflict that can come from coping with other individuals in your same space. My horses love their stalls, because that is their safe sanctuary, that is where they get special scratching and hugs, and visits from a little red haired girl who loves them and sings them songs.

Then comes my joy of returning to the house, feeding my human family and tucking precious children into bed, even though two are now taller than me. The world feels momentarily predictable and comforting in spite of devastation and tragedy. Hugging a favorite pillow and wrapping up in a familiar soft blanket, there is warmth and safety in being tucked in.

I’ll continue to search for those moments of epiphany whenever I’m frightened, hurting and unable to cope. I need a quiet routine to help remind me how precious it is to be here, looking for a sanctuary to regroup and renew.

I don’t need to look far…

(published a year ago in Country Magazine)

(published a year ago in Country Magazine)

It started innocently enough in April

It started innocently enough in April