There is safety in routine–predictable things happening in predictable ways, day after day, week after week, year after year. Somehow, dull as it may seem, the “norm” is quite comforting, like each breath taken in and let go, each heart beat following the next. We depend on it, take it for granted, forget it until something doesn’t go as it should.

Mornings are very routine for me. I wake before the alarm, usually by 5:30 AM, fire up the computer and turn the stove on to get my coffee water boiling. I head down the driveway to fetch the paper, either feeling my way in the dark if it is winter, or squinting at the glare of early morning sunlight if it is not. I make my morning coffee, check my emails, eat my share of whole grains while reading the paper, climb into my rubber boots and head out for chores.

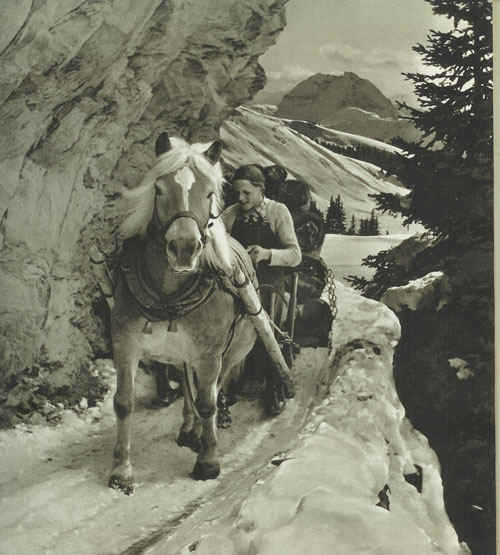

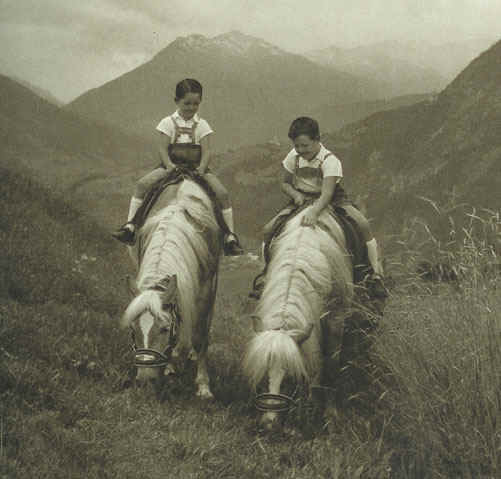

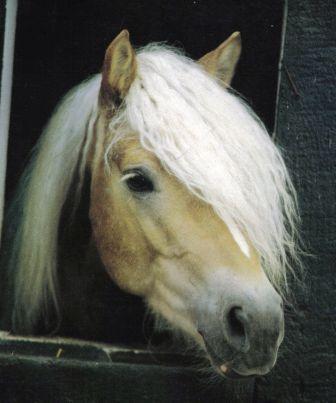

The same Haflinger voices greet me in the barn every morning, and I let our stallion in from his night outside in the pasture. He has his rituals too. We must do them together or nothing is quite right the rest of the day. He must inspect every corner of the enclosed area between pasture and barn door, marking each spot with urine or manure that he marked just 12 hours previously, 24 hours previously, 36 hours previously. Same spots, same marking to declare this “his” territory. He reinspects all of them one more time to make sure they smell just as they should and then content, he’s ready to come into his daytime stall and paddock while the rest of the horses go out for the day.

If I’m in a hurry and try to disrupt or speed up his morning routine, he is gracious about it but clearly it makes him grumpy and out of sorts. That evening, he’ll take the extra time to check every thing three times because I didn’t allow him his routine two checks in the morning. He’s truly obsessive compulsive to the point of an empty bladder and no more manure to be had. He simply goes through the motions, even though he has exhausted his “marking” supply. I can’t help but chuckle at the futility, but realize that this comforts him, gives him a sense of control and command. I’m really no different at all, emptying myself out in all kinds of futile rituals to give me a sense of “control”.

The other morning, as I was leading a mare and her colt out to our large outdoor arena for their daytime turnout, I was whistling to the wandering colt as he had his own ideas about where he wanted to be, and it wasn’t where I was leading. He was bucking the routine that his daddy so treasures, but in his young rebellion, was straying too far away from his mother who also called for him. 50 yards away, he decided he was beyond his comfort zone so whirled around, sped back to his mom and me, and traveling too fast to get the brakes on ended up body slamming her on her right side, putting her off balance and she side stepped toward me, landing one very sizeable Haflinger hoof directly on my rubber booted foot. Hard. Oh my. I said some words I’ll not repeat here.

I hobbled my way with them to the arena, let them go, closed the gate and then pulled my boot off to see my very scrunched looking toes, puffing up and throbbing. I still had more horses to move, so I started to limp back to the barn, biting my lip and thinking “this is no big deal, this is just a little inconvenience, this will feel better in the next few minutes” but each step suggested otherwise. I was getting crankier by the second when I passed beneath one of our big evergreen trees near the arena and noticed something I would not have noticed if I hadn’t been staring down at my poor sore foot. An eagle feather, dew covered, was lodged in the tall grass beneath the tree, dropped there as a bald eagle had lifted its wings to fly off from the tree top, probably to dive down to grab one of the many wild bunnies that race across the open arena, each vulnerable to the raptors that know this spot as a good place for lunch . The wing feather lay there glistening, marking the spot, possessing the tree, claiming the land, owning our farm. It belonged there and I did not–in fact I can’t even legally keep this feather–the law says I’m to leave it where I find it or turn it over to the federal government.

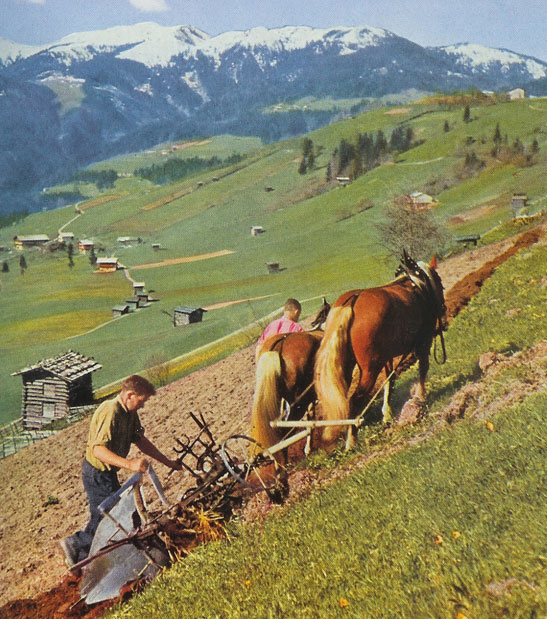

I am simply a visitor on this acreage, too often numbly going through my morning routine, accomplishing my chores for the few years I am here until I’m too old or crippled to continue. The eagles will always be here as long as the trees and potential lunches remain to attract them.

Contemplating my tenure on this earth, my toes don’t hurt much anymore. I am reminded that nothing truly is routine about daily life, it is gifted to us as a feather from heaven, floating down to us in ways we could never expect nor deserve. I’d been body slammed that morning all right, but by the touch of a feather. Bruised and broken but then built up, carried and sustained. Even pain brings revelation. Sometimes it is the only thing that does.

In late May, on our farm, there is only a brief period of utter silence during the dark of the night. Up until about 2 AM, the spring peepers are croaking and chorusing vigorously in our ponds and wetlands, and around 4 AM the diverse bird song begins in the many tall trees surrounding the house and barnyard.

In late May, on our farm, there is only a brief period of utter silence during the dark of the night. Up until about 2 AM, the spring peepers are croaking and chorusing vigorously in our ponds and wetlands, and around 4 AM the diverse bird song begins in the many tall trees surrounding the house and barnyard.

Fingers of twilight shadow

Fingers of twilight shadow